The Great (Linguistic) Reshuffle

Of dying dragons and breaching babelfish, and the dawn of the next Age of Discovery

Author’s note - if you’re a regular reader or listener of Infinite Loops, you know that we have a soft spot for new paradigms here at O’Shaughnessy Ventures. Chief amongst these is the concept of The Great Reshuffle. It’s the idea that our world is in the midst of an economic, social and cultural rearrangement - a feng-shui of epic proportions - largely propelled by the pervasiveness of the Internet in the 21st century, and a confluence of emerging technologies that are all ripening at the same time.

Our job as envoys of The Great Reshuffle is to unpack these changes alongside you - our dear OSV community - so we can together sharpen our mental models in preparation for optimistic future. Today’s essay, then, is firmly on trend. It was conceived on the back of three disparate pieces of information colliding (and getting cozy) in my brain -

1. The European ‘Age of Discovery’ (or Age of Exploration, depending on your sensibilities);

2. Balaji Srinivasan’s ‘The Network State’;

3. OpenAI’s launch of its new ‘multimodal’ AI model ‘GPT-4o’ in May 2024

This essay posits the thesis that we may be standing on the cusp of a new epoch for human exploration, fuelled by the dissolving of language barriers in the age of Large Language Models. The objective is not to present a definitive portrait of the future, but to illuminate one colourful timeline of how things may play out. As always, we hope this invites a kaleidoscope of varying responses from our readers - feel free to kick off in the comments section below. So without further ado, welcome to The Great (Linguistic) Reshuffle.

The Pope knew that the only way to stop them from fighting was to carve the world in half.

In 1494, still nursing its wounds from the Hundred Years' War, Europe found itself caught in a geographical vice grip. To the East, the Ottoman Empire cast a long shadow. Its scimitars still gleamed from the conquest of Constantinople just four decades earlier. The Ottoman Turks represented an overland blockade to the spice-laden lands of the East Indies, choking off the arteries of commerce that had long fed European coffers. To the West, the vast, untamed Atlantic stretched to the horizon and beyond, a liquid wall that had rebuffed explorers for centuries.

The continent was seemingly at the mercy of two unconquerable forces - trapped between a Turk and a wet place.

Iberian Sunrise

Yet, it was on the Western fringe of this landmass that the crucible of a new age was forming. On the sun-baked Iberian Peninsula, two kingdoms had emerged at the vanguard of maritime innovation and ambition. Their eyes were fixated on the edges of the Earth. Their astrolabes and compasses yearned for uncharted stars and unfamiliar winds, their ships poised to punch through the barriers that had long hemmed in their world.

Spain and Portugal, perched on the edge of the known world, were preparing to turn their shores into a launchpad for global domination.

Portugal, a small nation nestled on the Atlantic, had spent the better part of a century perfecting the art of exploration. Under the stewardship of Prince Henry the Navigator, Portuguese caravels had methodically probed southward along the African coast. Their mariners had diligently added miles of coastline to their mapmaker’s lexicon, one padrão (stone pillar) at a time.

Spain, on the other hand, was newly unified under the Catholic monarchs Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon. It was a rising power with grand ambitions. Fresh from the Reconquista - the centuries-long campaign to expel the Moors from the Iberian Peninsula - Spain sought new frontiers to conquer and new souls to convert.

The stage was set for fireworks between the two longtime neighbours and rivals. The spark would be provided by a Genoese adventurer named Cristoforo Colombo (known as Christopher Columbus to Anglo-Saxon buddies). Columbus had convinced Queen Isabella to finance his westward voyage to Asia, after having first been rejected by the Portuguese court. He had been steadfast in his belief that, given the spherical nature of the world, a quicker Westward sea route to India could be charted.

When he returned to Europe in 1493, he bore news of lands across the Atlantic, apparently convinced that he had found India (ignorant of the fact that he had really been the first European to set foot on the islands of the Caribbean). With his claim seemingly vindicated, his revelations rumbled through the European halls of power. Spain, emboldened by Columbus' discovery, prepared to stake its claim on whatever riches lay in the West. Portugal, which had claimed exclusive rights to the African route to India through papal bulls, now faced a rival in its quest for maritime supremacy.

The potential for conflict was immense. Both kingdoms, their coffers drained by years of war and exploration, saw in these new lands the promise of untold wealth. More than gold was at stake; this was a battle for the future of empires, for the souls of heathens to be converted, for glory everlasting. The tenuous balance of peace between the Iberian rivals again threatened to tip into chaos.

The Treaty

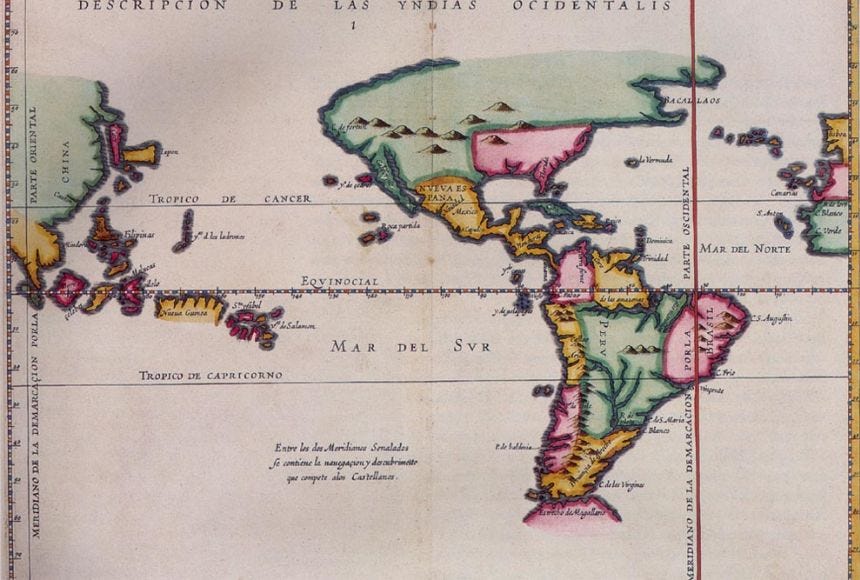

Enter Pope Alexander VI, born Rodrigo Borgia in Spain. As head of the Catholic Church, he wielded enormous influence (and as a Spaniard, he was not immune to the politics of his homeland). His solution to stave off the brewing crisis was audacious in its simplicity: a line drawn on a map, running north to south, 100 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands.

This invisible boundary became the ultimate real estate deal of the 15th century. It was a masterpiece of diplomacy, appeasing both parties while setting the stage for centuries of exploration and conquest. Spain received rights to lands west of the line, effectively granting them most of the Americas. Portugal secured an exclusive route around Africa, to the Middle East, India, and beyond.

This line in the embryonic world map would be enshrined in the Treaty of Tordesillas, signed on 7 June, 1494.

The Treaty did more than prevent war; it legitimised the concept of European dominion over distant lands and peoples. It was the legal and spiritual foundation upon which vast empires would be built, a document that would shape the destinies of millions of people across multiple continents.

As Spanish galleons and Portuguese caravels set sail towards an unseen finish line, they carried with them not just the hopes of kings and conquistadors, but the weight of a new world order. Tordesillas was the starting gun for the Age of Discovery. The map of the world would never be the same again.

The Age of Discovery

As ships sailed and colonies were founded, the Treaty revealed itself to be both more and less than its creators had intended. On one hand it was a framework for conquest, a license for exploitation, and a catalyst for cultural exchange on a scale never seen before. On the other, it was also ultimately unenforceable. Other European powers, hungry for their slice of the New World, would ignore the Treaty altogether.

"The sun shines for me as it does for others. I would very much like to see the clause of Adam's will by which I should be denied my share of the world."

- Francis I, The King of France (1515)

It was as if the Pope's line had not divided the world, but rather unfurled it like a scroll, inviting the boldest and most ambitious to write their names upon its blank spaces. The dragons of the Great Unknown stood no match against the marauding mariners from Iberia and beyond.

Over the next two centuries, European powers raced to paint the plains of the world in their own colours. Portugal's Vasco da Gama charted the fabled sea route to India in 1498. Spain's conquistadors pushed deep into the American continents. The Dutch, led by intrepid navigators like Willem Janszoon, began sketching the shores of Australia in 1606. English explorer James Cook's voyages in the late 18th century finally unveiled the vastness of the Pacific, charting New Zealand and eastern Australia with remarkable precision. Meanwhile, French expeditions penetrated the North American interior, mapping the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River.

The world map gradually transformed from a patchwork of conjecture and myth into an increasingly detailed representation of global reality. The Age of Discovery had not just expanded European empires; it had fundamentally reshaped humanity's understanding of the planet we inhabited, shrinking the world even as it revealed its true immensity.

A little over a century after Columbus had returned from his groundbreaking voyage, previously disparate compartments of the globe began to seep into one another. By 1600 the great Columbian Exchange was in full swing, with crops, animals, and diseases crossing oceans and reshaping ecosystems. Potatoes and maize from the Americas revolutionised European agriculture. African slaves toiled on Caribbean sugar plantations. Silver from the Americas fuelled a global trading network that reached as far as China.

Suddenly, the world seemed both vastly larger and surprisingly small. A ship leaving Seville might touch four continents before returning home. A Portuguese trader in Nagasaki could discuss the latest news from Lima. The Jesuit Matteo Ricci could explain Euclid to the Chinese emperor, while Incan gold adorned Spanish churches.

This newfound interconnectedness brought profound changes. Ideas and technologies spread rapidly. The Renaissance gave way to the Scientific Revolution as European thinkers grappled with the flood of new information about the world's peoples, flora, and fauna. New forms of economic organisation, like joint-stock companies, emerged to manage the risks and rewards of global trade.

Yet this shrinking world came at a terrible cost. Indigenous populations in the Americas were decimated by disease and conquest. African societies were ravaged by the slave trade. Ancient ways of life were upended as the world's ecosystems and economies became increasingly intertwined.

As the 19th century dawned, the map of the world had been filled in, its blank spaces replaced by imperial claims and trade routes. The Age of Discovery had given way to an age of global connections, for better and for worse. The world, once vast and mysterious, had become a single, interconnected system - smaller, perhaps, but infinitely more complex.

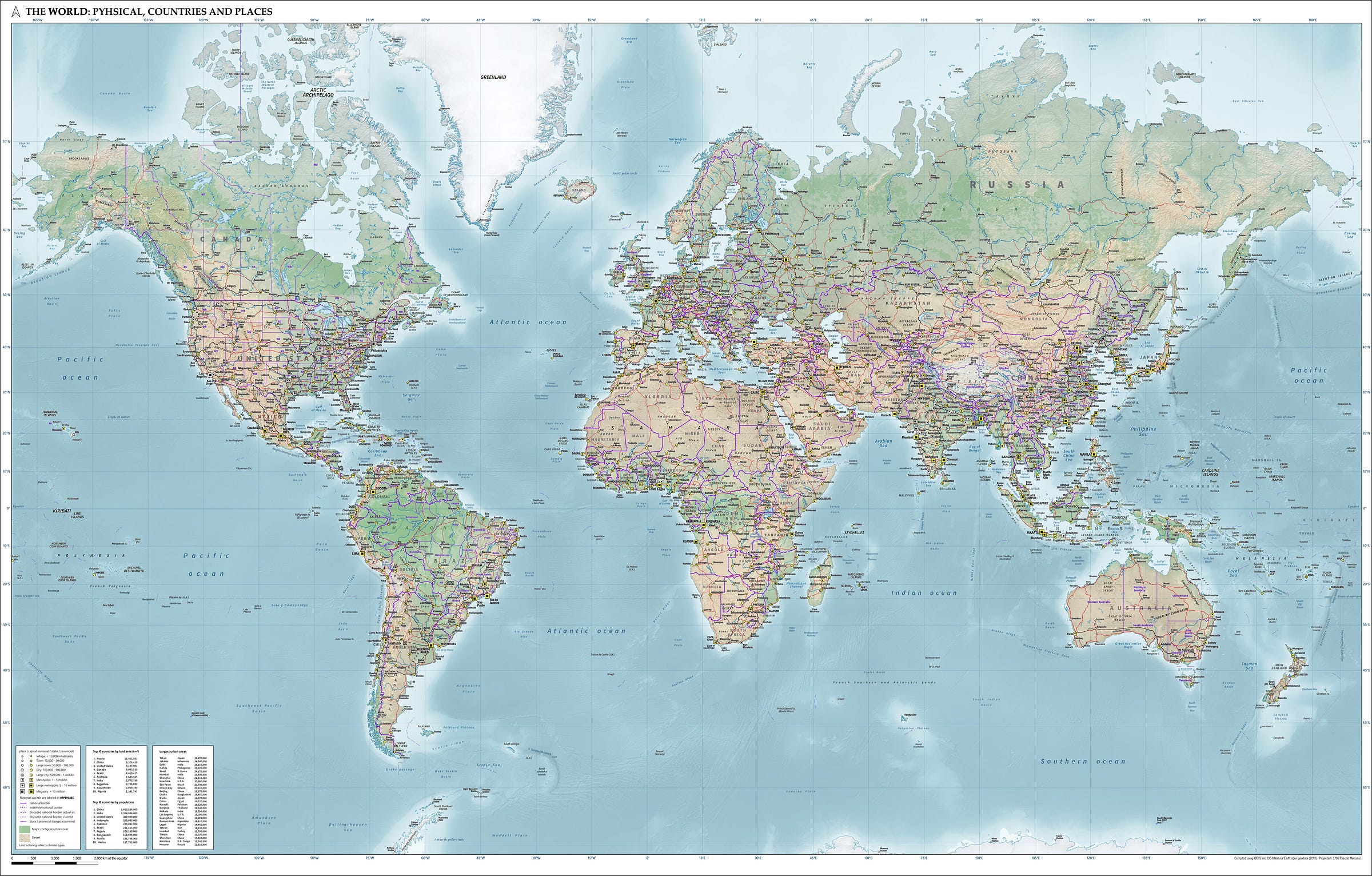

Cloud Cartography

The face of the world today owes much of its wrinkles, freckles, lines and scars to the Age of Discovery. Our geopolitical boundaries, our economic systems, even our diets bear the indelible marks of those centuries of exploration and conquest. The physical map, once riddled with terra incognita, now lies fully charted, its contours known down to the last island and inlet.

We seldom pause to marvel at the world map adorning our walls or glowing on our screens. Its completeness feels almost mundane, a given in our age of satellite imagery and GPS. Yet this comprehensive cartography, now taken for granted, represents one of humanity's greatest collective achievements. It is the fruit of centuries of daring exploration, scientific innovation, and often deadly perseverance. Countless souls were lost to uncharted seas, unmapped jungles, and unexplored mountain ranges in the quest to fill those blank spaces (to say nothing of the perils of indigenous people that had to make room for their unruly visitors).

The development of tools like the marine chronometer and theodolite revolutionised navigation and surveying, turning the art of mapmaking into a science. The sextant, the chronometer, and advanced navigational mathematics were all born from the pressing need to know precisely where we are on this pale blue dot.

Today, we reap the benefits of this fully mapped world in myriad ways: from the GPS that guides us home, to the digital maps that allow us to hail cabs and order take-out; from the weather forecasts that predict hurricanes, to the geopolitical awareness that shapes international relations. From disaster relief to international shipping to international travel, cartographical progress has done more than fill in the blanks on our maps—it has fundamentally shrunk our world, transforming a vast, mysterious planet into a known, navigable sphere.

Yet in the digital age, our concept of planetary "smallness" has flipped.

Our world has shrunk not through the charting of physical terrain, but through the invisible threads of the internet. We navigate a new geography - divided by the Earth but united by the cloud - where distance is measured in clicks rather than leagues, and where information flows as freely as the trade winds that once carried Portuguese carracks across vast oceans.

But just as the European powers of the 15th century lived in a time of cartographical blindness, largely unaware of the vast continents that lay beyond their horizons, we too are oblivious to the real limits of our digital exploration. We sail the seas of the Internet, believing them boundless, unaware of the shores we cannot see.

These digital vistas are not marked by coastlines or mountain ranges. Instead, they manifest in myriad, subtle ways. They are the niche subreddits, hidden like secluded coves, teeming with life yet unknown to the broader digital world. They are the walled gardens of social media companies, each a virtual continent with its own laws and customs, often impenetrable to outsiders. They are the political echo chambers, like digital archipelagos where like minds cluster, isolated from opposing views.

But superseding all these boundaries, more insurmountable than any digital wall or algorithmic filter, are the linguistic frontiers.

Lingua Incognita

"The limits of my language mean the limits of my world."

- Ludwig Wittgenstein

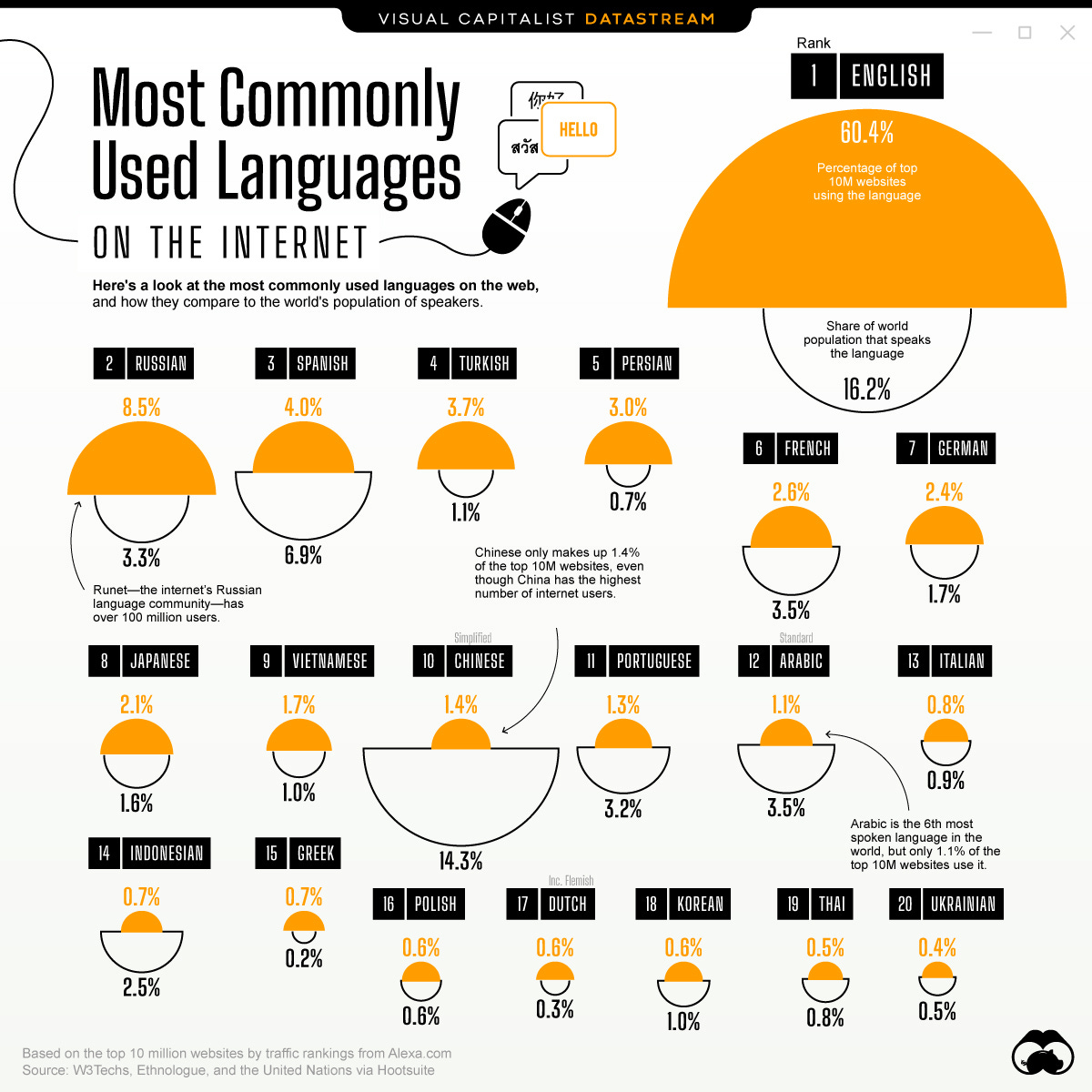

Languages are the rivers, mountains, and deserts of our digital world. They divide the internet into distinct territories, each with its own culture, memes, and spheres of influence. The Chinese internet, the Russian internet, the Arabic internet - each is a vast realm, largely invisible and inaccessible to those who don't speak the language.

This linguistic balkanisation of the Web (which doesn’t even include the billion+ people living behind the Great Firewall of China) creates invisible barriers to the free flow of information and ideas. It shapes our world-views, influences our access to knowledge, and impacts global discourse in ways we're only beginning to understand. Just as the early explorers could only guess at what lay beyond the horizon, we can only imagine the vast swathes of the internet that lie beyond our linguistic reach.

The disparities between linguistic internets are stark and consequential. Take, for instance, the Chinese internet – a vast digital ecosystem largely isolated from the Western web. When COVID-19 first emerged in Wuhan, early warnings and on-the-ground reports circulated on Chinese social media platforms like Weibo and WeChat weeks before the news broke in the English-speaking world. Could access to this crucial information, trapped behind the language barrier, have accelerated global preparedness to the virus?

Similarly, during the 2011 Arab Spring, Twitter and Facebook were awash with real-time updates in Arabic, providing invaluable insights into the unfolding revolutions. Yet many Western observers, reliant on delayed translations, struggled to grasp the nuances and rapid developments occurring on the ground.

In the realm of technology, Japanese Twitter has long been a hotbed of cutting-edge AI and robotics discussions, often months ahead of similar conversations in English-speaking tech circles. Innovations and breakthroughs discussed in Japanese frequently take time to percolate into the anglophone tech discourse, potentially slowing global advancement in these fields.

Even in entertainment and popular culture, linguistic divides create parallel universes of content. The Korean web, for example, buzzes with discussions about K-dramas and K-pop long before these phenomena break into global consciousness. By the time "Squid Game" became a worldwide sensation, Korean netizens had already dissected its themes, critiqued its execution, and moved on to the next big thing.

These examples underscore a crucial point: valuable information, innovative ideas, and cultural phenomena often remain sequestered within their linguistic domains. A Spanish-speaking scientific forum might hold the solution to a problem puzzling English-speaking researchers. Russian social media could be discussing a novel approach to climate change mitigation unknown to French environmentalists. Indian theology could be a solution to Nigerian ennui. The linguistic barriers of the internet don't just separate us – they hinder the global exchange of knowledge, ideas and even goods and services, creating a siloed digital world that could be economically, socially, and culturally richer if we could just understand each other better.

Over the past three decades, the commercial Internet has radically transformed our world, compressing time and space in ways that were previously unimaginable. It’s allowed us to make connections, purchase products, and find love, work, and entertainment outside of our immediate vicinities. The irony of the Internet Age is that today it may be easier for you to leave the physical place of your birth than the digital domain outside your native tongue.

But we are perhaps at the onset of a new era. Just as advances in shipbuilding and navigation once opened up the physical world to exploration, emerging technologies hold the potential to bridge these linguistic divides. We might be witnessing the dawn of an Age of Discovery v2.0, one that could illuminate the expanse of uncharted digital terrain around us and reshape our understanding of ourselves. Again.

Deus in machina

The seeds of this essay were planted on 13th May of this year, when OpenAI1 announced the launch of its flagship new AI model - GPT-4o, or ‘Omni’, for short. In their own words:

The company’s (non-profit’s?) messaging around GPT-4o emphasised the unprecedented ‘multimodal’ and ‘multilingual’ capabilities of the new model2.

The former just means that Omni can seamlessly process audio, visual, and text-based instructions and generate outputs across any of those modalities.

Most important for us is the latter, where GPT-4o was hailed as a polyglot par excellence, having been trained on datasets that include 50 languages (covering 97% of the world’s speakers). Compared to older models, the new kid on the block had made significant strides forward in its reasoning capabilities for languages outside of English. Beyond mere translation, a post-Omni ChatGPT can even understand tone, inflections, context, and cultural nuance when it comes to multilingual comprehension. All told, the Omni launch was intended to be a peek into the “future of interaction between ourselves and machines.”

Amongst the pageantry around the launch event were two demos that caught my attention. One showed how ChatGPT could ‘look’ through the camera lens and ‘call out’ the names of everyday objects in Spanish. Another demonstrated how it could function as a ‘real time’ translator for two people in the same room who didn’t speak the same language.

While neither of these are particularly earth-shattering (given that there are apps and services that do this already), the model itself was apparently far superior than anything else in the market up to that point with regards to its proficiency with audio translation.

And it was also far superior to OpenAI’s incumbent text-to-audio service Whisper.

Given how fast the AI arms race is progressing, it’s likely that these rankings have been reshuffled already. But back in May, OpenAI was proudly touting its shiny new model as the apex of instant, machine-based, language translation.

Among the commentary following Omni's release was a viral tweet highlighting the immediate impact of the event on Duolingo's share price - an apparent market verdict on the future of the world's biggest language learning app in an age of real-time AI translation…

…which, though it turned out to be a simple case of markets being markets…

…bore an implication that was provocative enough to consider deeply (and perhaps even spawned a self-fulfilling prophecy)

In other words, that tweet clocked high on my ‘Hmmm that’s interesting’ meter.

To be clear, the implication that language learning will be either replaced or supplemented by conversational AI interfaces is not itself controversial. In fact, Duolingo itself pioneered the integration of GPT-3 and GPT-4 in earlier versions of its app to perform the role of a personalised on-demand language tutor for its users.

What is controversial, however, is the idea that we may not need to learn foreign languages at all in a post-AI world.

Consider, for instance, that the new and improved GPT-4o allows you to do things like give ChatGPT an instruction in English to tell you a story in Hindi (which it does a pretty good job at). It lets you post a link to a Youtube lecture in French, and receive detailed notes on it in Japanese. You can take a picture of a sign in Spanish outside the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona, and ask for an audio explanation in Vietnamese. That’s the hope once it’s fully rolled out anyway.

OpenAI claims that its new model can orchestrate these requests in near real-time, with minimal loss in fidelity, with a performance that will likely get better, cheaper, and faster with each new release. Other multimodal LLMs like those from Anthropic (Claude), Google (Gemini) or Facebook (Llama) offer similar capabilities, with promises to preserve localised context and cultural nuances of individual languages.

All to say, that there may be something both very interesting and very important happening at the intersection of language and AI. If you don’t see it yet, if none of these developments or demos have aroused your curiosity so far, especially given that we live in an era of Google Translate, that’s understandable.

It’s also a sign that Douglas Adams was right.

The Subtitle Economy

Buried in the heap of gold that is Douglas Adams’ posthumously released Salmon of Doubt, is a particularly shiny nugget depicting the author’s observations on how humans typically grapple with new technologies:

“I've come up with a set of rules that describe our reactions to technologies:

1. Anything that is in the world when you’re born is normal and ordinary and is just a natural part of the way the world works.

2. Anything that's invented between when you’re fifteen and thirty-five is new and exciting and revolutionary and you can probably get a career in it.

3. Anything invented after you're thirty-five is against the natural order of things.”

As someone only just on the ~wrong side~ of 30, it feels strange to use the verbiage of in-my-lifetimes, but *clears throat* in my lifetime, we almost certainly take for granted the ubiquity of instant language translation.

We barely register how, with a few bleep-bloop-bleeps on our keyboards, we can open up portals into other worlds.

We don’t even blink before whipping out our translation apps to haggle with a street vendor in a foreign country. Or marvel at the ability to learn a new language on our phones as a way to stave off boredom on the commute to work. Or appreciate how we can be moved by the words in books, shows and movies that were originally cast in languages that are not our own.

Instant translation is a gift of modernity that lubricates the wheels of the world in more ways than we realise. It is a gift that our ancestors would have equated with its weight in gold. Let’s return briefly to our Iberian friends from the start of this essay.

Back in the 16th century, having just stepped foot into Aztec-ruled Mexico, the Spanish conquistadors were faced with a formidable roadblock. Confronted with an Aztec Empire that was as incomprehensible to them as their steel weapons were to the natives, Hernán Cortés had to enlist the services of a legendary interpreter - a woman known as La Malinche - to negotiate alliances with rival indigenous groups, to understand the fault-lines of the Mesoamerican political landscape, and ultimately to engage in a tenuous diplomacy with the Aztec emperor Moctezuma II.

A controversial figure, La Malinche is remembered as the architect of the linguistic bridge that allowed the Spaniards to plant their flag in the New World. In our species-long quest to build more such linguistic bridges between ourselves, La Malinche may well be the great-great-great-great-great-great grandmother of the Large Language Model.

LLMs are the latest sequential step in our employing of specialised intermediaries to play the role of translators, a task for which computers have found themselves to be extraordinarily capable in recent times. Generative AI is the next chapter in a journey that began as far back as the 1950s, amidst the frost of the Cold War, when the Georgetown-IBM experiment first offered a glimpse into the potential of machine translation (albeit for a machine with a vocabulary of just 250 words and six grammatical rules).

“A girl who didn’t understand a word of the language of the Soviets punched out the Russian messages on IBM cards. The “brain” dashed off its English translations on an automatic printer at the breakneck speed of two and a half lines per second,” — reported the IBM press release.

The fruits from Georgetown would be harvested in the 1970s, when SYSTRAN launched one of the world’s first machine translation companies as part of their efforts to decrypt Russian text for the United States Air Force. IBM would spearhead the move into statistical translation in the 1990s, before Google made instant translation a ubiquitous commodity with the launch of Google Translate in 2006 (allowing millions of teenagers around the world to understand the lyrics to Gangnam Style).

Many of these nascent translation ventures were imperfect, sometimes comical, often clunky, but ultimately good enough to get us from A to B. It’s only really in the 2010s, when we began to transition from machines that could compute to machines that could ‘think’ (via neural networks), that the game has levelled up. From Google to DeepL to OpenAI and everyone in between, the LLM era has exponentially increased the natural language processing capabilities of computers.

Modern AI translation systems use neural networks, specifically a type called transformers. Unlike previous statistical methods, these systems don't just match words or phrases; they understand context and nuance. For example, when translating the English phrase 'I'm feeling blue' to French, the system recognises this as an idiomatic expression and might translate it to 'J'ai le cafard' (literally, 'I have the cockroach', a French idiom for feeling down), rather than a literal colour-based translation.

This contextual understanding allows for more natural, accurate translations across a wide range of languages and domains. It’s the result of machines getting smarter, and catching up to the linguistic capabilities of their human counterparts at breakneck speed.

It means we are getting closer to crossing the chasm from science fiction to science fact, harking back to another one of Douglas Adams’ literary inventions - The Babel Fish - courtesy of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy:

“The Babel fish is small, yellow and leech-like, and probably the oddest thing in the Universe. It feeds on brainwave energy received not from its own carrier but from those around it. It absorbs all unconscious mental frequencies from this brainwave energy to nourish itself with. It then excretes into the mind of its carrier a telepathic matrix formed by combining the conscious thought frequencies with the nerve signals picked up from the speech centres of the brain which has supplied them.

The practical upshot of all this is that if you stick a Babel fish in your ear you can instantly understand anything said to you in any form of language. The speech patterns you actually hear decode the brainwave matrix which has been fed into your mind by your Babel fish.”

LLMs might prove to be the perfect habitat for rearing Babel fish3. And with the launch of multimodal, multilingual LLMs like GPT-4o and others, humanity is preparing to set sail into Babel fish-infested waters.

Age of Discovery v2.0

But where are we going? Well, the past provides a precedent.

If early navigational tools like the astrolabe, the compass, and the sextant helped to expose the edges of the Earth, and sophisticated shipping vessels helped colonial explorers to explore every inch of it, it was the Internet that finally killed the ‘idea’ of geographical barriers.

Similarly, three pertinent questions to ponder over the coming decade are:

- to what extent will the application of LLMs succeed in bridging our linguistic divides - both online and offline?

- will AI meaningfully kill the ‘idea’ of language barriers in the same way that the Internet killed the idea of geographical barriers?

- and if so, how much of the world is about to open up to us - individually, collectively, culturally, socially and economically?

None of these questions will be answered overnight, but given the pace of progress in the field of deep learning over the last decade, it’s fair to characterise the Generative AI era as another Padrão - a stone pillar in the linguistic dirt - a tangible marker of progress in our mission to explore the territory beyond our linguistic confines.

The early explorers are already rounding the Cape.

Roblox, the virtual world and gaming platform, announced that they had built an in-house LLM, and were using it to enable ‘real-time AI chat translations’ so that people who spoke different languages could communicate seamlessly with one another in their immersive 3D landscapes. Their custom multilingual model can facilitate direct translation between any combination of the 16 languages they currently support.

The feature has already driven ‘stronger engagement and session quality’ for the 70 million global users on the Roblox platform. Their CTO, Daniel Sturman, declared that “The ability for people to have seamless, natural conversations in their native languages brings us closer to our goal of connecting a billion people with optimism and civility”.

This same notion also extends to the wider creator economy. Popular Youtubers like Mr. Beast have realised that they can vastly expand their Total Addressable Market (and their subsequent monetisation potential) by dubbing their videos in languages outside of their native tongues. Mr. Beast, the world’s biggest Youtuber, has even launched his own company that delivers this as a service for other creators, allowing them to simultaneously publish their videos in multilingual form.

Here’s Samir Chaudry from the popular Youtube channel Colin and Samir, recently articulating the impact of AI dubbing on the retention of their viewers.

The 2024 Indian Premier League (the world’s premier club cricket competition) saw AI being used for the first time to dub the words of international commentators in Hindi so they could be accessible to the billion+ audience in India. Steve Smith, current analyst and former Australian cricket team captain, said at the time:

“Namaste India! Being a part of the StarCast with such a stellar line-up of commentators has been a thrill for me. More importantly, my family, friends, and fans around the world got very excited after the hologram clip went viral last year. This season I’m part of another breakthrough technology where you’ll hear my IPL insights in Hindi. I’ve received some great feedback from fans, and I’m excited to connect with millions of viewers through the Star Sports Hindi feed.”

But translation isn’t just for fun and games. A recent study from MIT’s Sloan School looked into the effects of better machine translation facilities on the volume of e-commerce on digital platforms. Researchers found that improvements in machine translation increased international trade by 10%. As Wharton School professor Ethan Mollick pointed out, translation caused “the same effect as shrinking the world by 25%”.

Another groundbreaking paper from May of this year demonstrated how researchers had assembled a ‘virtual company’ staffed by AI agents employed in the task of translating literary books. These agents - called TransAgents - were given specific roles and tasks like ‘CEO’, ‘junior editor’, ‘translator’, ‘proofreader’ et al, effectively mimicking the environment of a real publishing company. The thesis behind this approach was to leverage the ability of LLMs to tackle the complexities of literary translation, which pose a different kind of style/eloquence challenge than ordinary plain text.

The study found that readers preferred the accuracy and authenticity of the TransAgent versions of translated Chinese novels over the ones translated by GPT4 or manually by humans. It opens to door a world where the ‘beauty and depth of literature transcend linguistic boundaries’.

Is it all just future-looking business stuff?

Nope.

Outside of strictly commercial applications, AI is proven itself integral to historically significant linguistic pursuits too. It is being used to unravel the mysteries of the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Herculaneum papyri, two ancient pieces of text that have confounded researchers since they were discovered over 70 and 270 years ago, respectively.

Advanced machine learning algorithms have helped to identify linguistic patterns in these documents, giving us clues about their authorship, and, in the case of the Herculaneum scrolls, confirming that the Ancient Romans did indeed love the colour purple and the taste of capers. These breakthroughs have arrived only in the past half-decade, increasing the likelihood of us being able to open up a fresh dialogue with the past.

AI also gives us a way to preserve the present for the future. Outside the risks of biodiversity loss, the 21st century is in the throes of a different kind of extinction that perhaps doesn’t pack the same guttural punch to our socioeconomic sensibilities. Of the world’s ~7000 native languages, an estimated 90% are expected to be extinct by 2050, with roughly one language dying out every two weeks.

It is tricky to calculate the true costs of a mass extinction event of this scale. We are not just staring at a loss of words, but entire worldviews that have been crystallised in these linguistic systems for millennia. Every month we are impoverished by the evaporation of discrete cultural knowledge, of observations of environmental phenomena, of collective wisdom and oral histories that have accumulated over generations.

As the world moves towards a linguistic consensus, we risk losing a little bit of what makes us, us. It should be no surprise then that LLMs have become a potent weapon in the arsenal of linguistic conservationists everywhere.

There are scores of efforts underway worldwide to train AI models on local language datasets - using text, speech and video to preserve many of the world’s endangered languages in digital amber. This has the potential to increase the representation of ‘low resource’ languages on the global Internet i.e. languages that are spoken by many people in the world but don’t have a strong digital footprint. In theory this means that:

you could record a podcast on indigenous fishing techniques with a Sami fisherman residing in rural Lapland, and help spread that knowledge to the English-speaking world

you could build a digital neobank product exclusively for the 80 million strong cohort of people that speak Tamil in India, allowing them to engage with the product through their phones via voice, text, or video-based messaging

you could create a global online book club to discuss (translated) Polish literature, where everyone chats with each other using a keyboard trained on their native language

The AI genie is out of the bottle. Similar to how the Internet changed our lives in millions of unpredictable ways, it’s impossible to say for sure what the second or third order effects of super-powered machine translation will be. Some would say, at the very least, we have a chance to learn from our past.

Redesigning The Tower

On one hand, we could be standing on the precipice of an epic era of global collaboration, built on the foundations of liberated remote knowledge and real cultural empathy.

We could see more examples like Japan’s lung-bursting ascent into industrialisation in the 19th and 20th centuries, fuelled by the translation of 10,000 European technical books on everything from medicine to astronomy to physics, chemistry, geography, and military science.

We might witness the birth of more institutions like the Toledo School of Translators, which ignited a knowledge revolution in 12th and 13th century Europe via the translation of a treasure trove of Arabic texts into Latin. This compendium - which included the works of Aristotle, Plato, Ptolemy and Euclid - planted the seeds of Europe’s eventual Renaissance.

Or maybe we will see the emergence of new founding memes and myths - a return to the monoculture that has dissipated with the fracturing of mass media? Something resembling the spread of Buddhism through East Asia on the back of Kumārajīva’s translation of the Buddhist Sutras into Chinese? Or the creation of documents like the translated King James Bible, which transcended religion and altered the fabric of English language and culture forever.

What would a Rosetta-Stone-as-a-service look like?

What would a ‘subtitle-for-everything’ economy feel like? (eg: Infinite TAM for the world’s best creators; Small businesses describing their products to customers worldwide, handling international inquiries, and navigating export regulations - all without hiring multilingual staff)

How would these changes impact the Internet? How could it spill over into the offline world? What inventions are now inevitable?

🤷♂️🤷♂️🤷♂️

It’s hard to say for sure. And there’s every chance it won’t all be rosy. We can again gaze into the cheat sheet of history for clues on how this could play out. In fact, perhaps the most famous instance about the consequences of linguistic uniformity (or lack thereof) can be traced back to the pages of the Bible.

The story of the Tower of Babel - recorded in the Book of Genesis - is both a cautionary tale against the hubris of man, and an appeal to (linguistic) diversity. It follows the journey of Noah’s descendants after the devastation of The Great Flood, and it’s also short enough to replicate here in it’s entirety:

Now the whole earth had one language and the same words. And as they migrated from the east, they came upon a plain in the land of Shinar and settled there. And they said to one another, “Come, let us make bricks, and burn them thoroughly.” And they had brick for stone, and bitumen for mortar.

Then they said, “Come, let us build ourselves a city, and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves; otherwise we shall be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.” The Lord came down to see the city and the tower, which mortals had built. And the Lord said, “Look, they are one people, and they have all one language; and this is only the beginning of what they will do; nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them. Come, let us go down, and confuse their language there, so that they will not understand one another’s speech.”

So the Lord scattered them abroad from there over the face of all the earth, and they left off building the city. Therefore it was called Babel, because there the Lord confused the language of all the earth; and from there the Lord scattered them abroad over the face of all the earth.

Like much of the writing in the Bible, the passage above is subject to multiple interpretations. In our case, we can extract from it a warning about our current infatuation with artificial intelligence, about creating digital experiences that veer uncomfortably close to playing God - those that are only a few standard deviations away from magic.

Perhaps we will also be similarly too bold, venturing too high, before we are brought back down to Earth. Perhaps will will rue the outsourcing of our thought to machines, which may perpetuate our worst biases and neuroses. Perhaps rather than preserving linguistic diversity, LLMs will plaster over the most colourful quirks of our various dialects, in favour of an efficient, brutalist homogenisation of global discourse.

Perhaps we won’t like what we find in a world of porous linguistic borders. Maybe nations of the Earth will want to preserve the right to record their own versions of world history, without subjecting our regional memories to a shared global consensus? Maybe we’d rather protect our own secrets.

A Babel-esque world where we can all “understand one another’s speech” might have different rules than the one we know. Maybe the dragons of the great unknown won’t be as friendly? Influence and Power might rear their heads in strange and unwelcome ways. Soft power might turn to hard power. Fringe might become mainstream.

Perhaps the socioeconomic earthquake will be too jarring, leading to an upsetting of incumbent status hierarchies? If multilingualism becomes commonplace, who will be the winners and losers? Where will leverage tilt across the translation value chain?

Time will tell.

It’s hard to make confident predictions given the pace of progress over just the past two years, progress that itself built upon the breakthroughs in transformer-architecture in the 2010s. The only safe bet is on the fact that the quality of AI outputs right now is the worst it’ll ever be, so just imagine what comes next?

Ten years from now, you might find yourself waking up in your Tokyo apartment, your AI assistant briefing you on Brazilian commodity news in perfect Japanese while you sip your morning coffee. Same as every morning, you hop on a video call with your Kenyan co-founder, the real-time translation so seamless you forget you're speaking different languages. For lunch, you step into your favourite Thai restaurant, your AR glasses instantly translating the handwritten specials board. Every Wednesday you might find yourself video calling your Parisian therapist for a check-up, your AI earbuds translating her advice flawlessly.

On your evening jog, you listen to a podcast in Hindi, understanding every reference as if you were born in Mumbai. Before bed, you help your son with his homework, effortlessly explaining a math problem originally written in Ancient Greek. Before bed, you're live-streaming a cooking class from a chef in Bogotá, following his rapid-fire instructions as if Spanish were your mother tongue.

If nothing feels out of the ordinary, on a day like this, that's probably a good indication that The Great (Linguistic) Reshuffle is in full swing.

Finding Hanno

In 1514, it had been 20 years since the Treaty of Tordesillas was signed, and almost a hundred since the Portuguese had begun systematically exploring the Atlantic coast of Africa.

The intervening period had been one of wanton exploration. The Kingdom of Spain had established its first permanent settlement in the Americas at Santo Domingo in 1496. By 1508, they had colonised Puerto Rico, and by 1511, Cuba. The Portuguese meanwhile had planted their flags on the coasts of Malabar and Malacca, and extended their maritime handshake as far as the Middle Kingdom of China. They had built a robust network of coastal bases all the way from Brazil to Mozambique to the Spice Islands in the East. The scope of European knowledge and influence had expanded exponentially in these two decades, reshaping the trade routes and power dynamics of the Middle Ages.

There was plenty of cause for celebration on the Iberian peninsula. To punctuate the breathtaking scale of their progress, the Governor of Portuguese India, Afonso de Albuquerque, saw fit to send back two exotic gifts for the incumbent Portuguese monarch King Manuel I. From Roger Crowley’s Conquerers:

“It was probably at the same time that he sent two rare animals to Manuel, one a white elephant, a gift from the king of Cochin, the second an equally rare white rhino, from the sultan of Cambay—the first live rhinoceros seen in Europe since the time of the Romans. The animals caused a sensation in Lisbon. The elephant was paraded through the streets and a fight arranged between the two animals in a specially built enclosure, in the presence of the king. The elephant, however, taking the measure of his opponent, fled in terror. In 1514, Manuel determined on a spectacular public projection of the majesty of his reign and his conquests of India. He delivered the white elephant to the pope under the command of his ambassador, Tristão da Cunha. A cavalcade of 140 people, including some Indians, and an assortment of wild animals—leopards, parrots, and a panther—entered Rome, watched by a gawping crowd. The elephant, led by his mahout, carried a silver castle on his back with rich presents for the pope, who christened him Hanno, after Hannibal’s elephants in Italy.

“At the papal audience, Hanno bowed three times and amused and alarmed the cardinals of the Holy Church by spraying the contents of a bucket of water over them. He was an immediate animal star—painted by artists, memorialized by poets, the subject of a now lost fresco and a scandalous satirical pamphlet, The Last Will and Testament of the Elephant Hanno. He was housed in a specially constructed building, took part in processions, and was greatly loved by the pope. Unfortunately, Hanno’s diet was ill-advised, and he died two years after his arrival, aged seven, having been dosed with a laxative laced with gold. The grieving [Pope] Leo X was at his side and buried him with honor.”

Despite his untimely demise, Hanno became a sensation, a living symbol of the new worlds that had opened up, and a tangible representation of how exploration was expanding European horizons. Just as the white elephant represented undreamed-of wonders from distant lands, our impending breach of linguistic barriers could unveil intellectual and cultural treasures we can scarcely imagine.

Who knows what we’ll see first?

If this journey takes the path of incremental progress, like the transition from sleek, wind-dancing caravels to imposing, wave-crushing carracks, we could see the discovery of faster sea routes to India i.e. improvements in familiar translation use cases built on the back of cheaper, faster, more accurate, multi-modal translation. This could include things like instant subbing and dubbing for all content, universal multilingual newsfeeds and RSS feeds, AI-assisted keyboards, multilingual voice assistants (that we don’t just click by accident), contextual advertising, wireless translation ear-pods, translation plug-ins for remote workers, and more. The second and third order effects of these alone merit another essay.

Outside of steady improvement, there remains the possibility of a world-altering discovery in the coming years. At some point someone’s going to ‘discover’ America. Who knows what that will mean in practice - maybe a brain machine interface that does true ‘real-time’ offline translation, changing the face of global travel and work. It could be the documentation of an indigenous conservation practice that unlocks the conundrum of global climate change. Or it might be the excavation of some ancient parchment that challenges our understanding of ourselves.

If the digital map was the logical end to the first Age of Discovery, what is the equivalent for translation? Imagine what the explorers of antiquity would have given to have a perfectly mapped representation of Earth in the palm of their hands, where with a few swipes of their fingers they could get a precise location of where they were in the world with instructions and timelines on how to get to their destinations. What will be the Google Maps of the Age of Discovery v2.0, a product that is so outrageously revolutionary, so indispensably useful, so ubiquitous to the point we take it for granted, that it would be offensive to the sensibilities of colonial explorers who had to figure out how to navigate the world ‘in the dark’. (NB: I don’t think Google Translate is the Google Maps of translation, yet).

And finally, once these artificial brains are ready, in what body will they fit most snugly? What will be the most natural interfaces and form factors of the AI era? Smartphone apps? Browser plug ins? Specialised earpieces? Or something else entirely.

Replicating the immortal words of Ernest Hemingway in response to the question of how he went bankrupt, the AI translation era has the makings of a revolution that will occur in two ways - “Gradually, then suddenly.”

As the caterpillar of humanity wraps itself in an AI cocoon, there’s no telling what kind of mysterious creature will emerge on the other side. Here’s hoping that, at the very least, we’ll be able to understand what it’s saying.

Footnotes

OpenAI is certainly not the only pedlar of digital divinity, nor is it the undisputed clubhouse leader across every facet of LLM performance. However, the company (or non-profit?) has a reasonable claim to Main Character status in the current Generative AI Extravaganza. It owes this primarily to the groundbreaking release of its flagship ChatGPT product in November 2022 that exposed much of the world to the quasi-magical potential of Large Language Models for the first time. As a result, its launch events have become somewhat of a bellwether for the AI industry, revealing clues about its future much in the same way that Steve Jobs would do for the smartphone industry on stage at Apple’s WWDC at the height of the mobile revolution.

If you’re the type of person who hasn’t kept up with contemporary AI lore or you’re the type of person whose eyes glaze over at the mention of the Newest AI Whatever, all you need to know is that the current frenzy around Artificial Intelligence is largely based on the novelty and potential of Large Language Models (LLMs). You can think of LLMs like digital brains that have been trained on oceans of data (text, websites, audio files, computer code etc), and provided with instructions on how to make sense of that data. While not capable of ‘thought’ in the truest sense, LLMs are able to make probabilistic guesses about what should come next in a sequence of words. Because they’ve been trained on an unfathomably vast quantum of data, the responses they generate can often resemble an output akin to human-level intelligence or even human-level creativity, as tools like ChatGPT and Midjourney loudly demonstrated when they bulldozed into the tech zeitgeist almost two years ago

Even if you subscribe to the view of people like Noam Chomsky, who insist that ‘LLM’s teach us nothing about language’, it doesn’t mean that the current wave of generative AI can’t push us towards new horizons for machine translation. LLM’s might only represent the mathematical application of linguistic inputs (vs an innovation in language per se). But that’s enough to make them dangerously useful.

ChatGPT was not the first time we typed things into a box on the Internet requesting a computer to retrieve some piece of information, but it exponentially expanded the palette of skills that a capable digital assistant could be expected to possess going forward. We can reasonably expect the same paradigm shift when it comes to multimodal AI-propelled translation over the coming years.

Sources & Further Reading

Hello GPT-4o by OpenAI

How Language Models Work by Dan Shipper

Mapping the Mind of a Large Language Model by Anthropic

Talking About Large Language Models by Murray Shanahan

Noam Chomsky: The False Promise of ChatGPT

Despite Their Feats, Large Language Models Still Haven’t Contributed to Linguistics by Mohamad Aboufoul

The Network State by Balaji Srinivasan

UNESCO’s Memory of the World Programme

Climbing towards NLU: On Meaning, Form, and Understanding in the Age of Data

A history of machine translation from the Cold War to deep learning

Are Inventions Inevitable? by William F. Ogburn and Dorothy Thomas

Acknowledgments

A big thank you to my OSV teammates Ed William and Liberty for reading through early drafts of this and sharing their feedback. Next beer on me.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Outside of OSV, Rahul Sanghi is the co-founder and writer of Tigerfeathers, where he’s building a time capsule for 21st century India. He doesn’t know why he’s writing this in third person, but whatever.

This is great 💚 🥃

A+ 🫡