Welcome back to the Creativity Diaries. If you enjoy the below, you can also explore our previous instalments on David Byrne, Salvador Dalí, Tchaikovsky, David Lynch, and Alfred Hitchcock.

The year is 1977. A young musician named Wayne Jobson leaves the lush green hills of St Ann, Jamaica, and heads south to Kingston. For the first time in his life, he is going to step inside the Black Ark.1

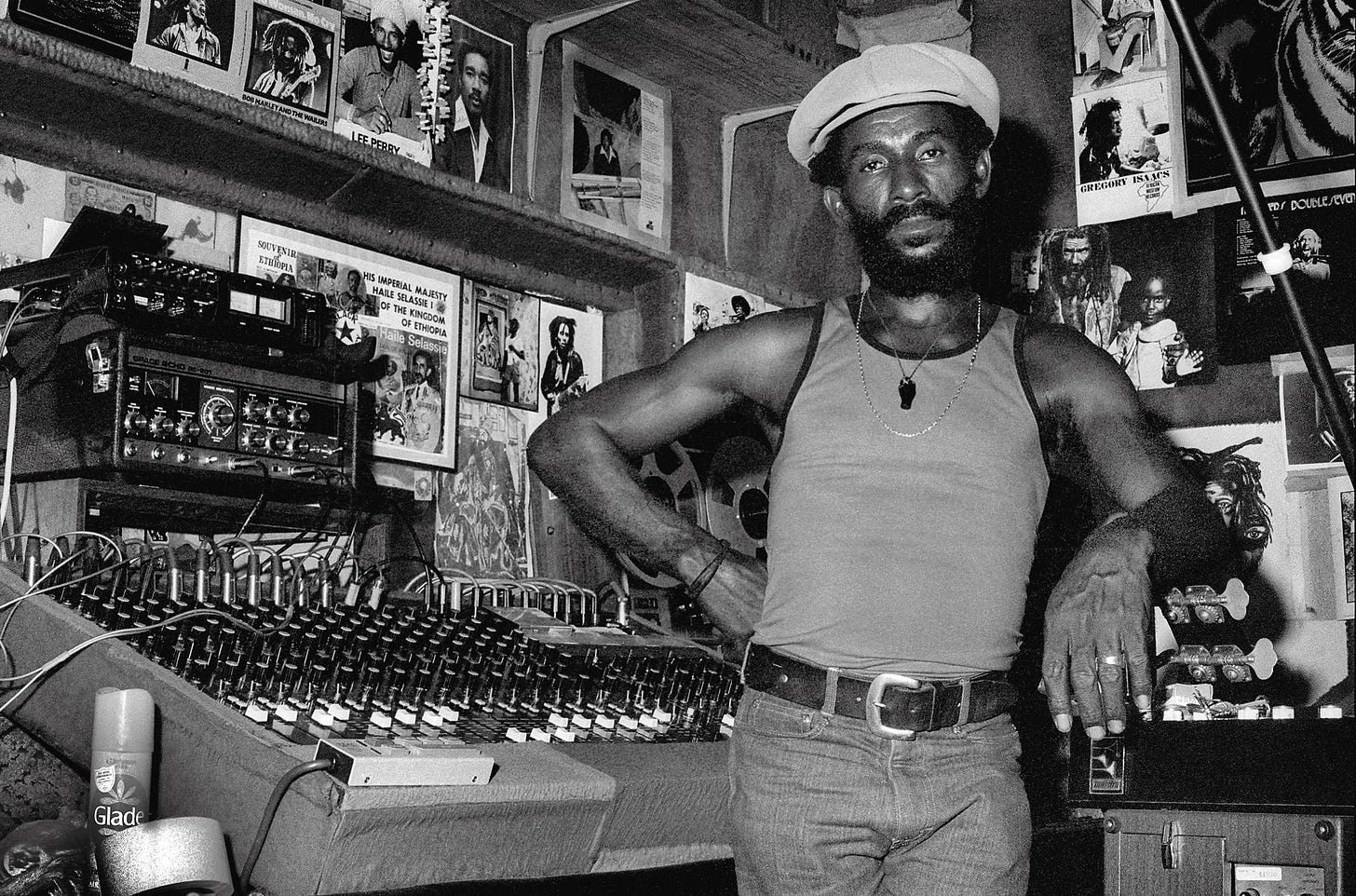

Every kid in Jamaica who cares about music knows the stories. The tiny backyard studio in Washington Gardens that somehow sounds like the center of the universe. And every kid has heard of Lee “Scratch” Perry, the eccentric firebrand who calls it home. Perry is famous for coaxing otherworldly textures out of the cheapest, most battered equipment on the island. He’s also famous for being, by any normal standard, completely bananas.

Jobson knows the reputation. He doesn’t know what it will feel like from the inside.

He’s there as a working musician, hired to play a session for the English soul-singer, Robert Palmer. The Englishman is there on his own pilgrimage to Perry’s temple. Like many before him, he wants to harness whatever invisible force animates the Black Ark.

Jobson is greeted by a bizarre scene. A pineapple stands proudly in front of a rattling fan, its purpose unclear — some sort of scented air-conditioning? The walls are dense with symbols and pornographic images. And there, perched in an elevated control room, is the high priest himself, a diminutive figure in full shamanic mode, bouncing behind the desk, pounding on the perspex window to bark instructions at the musicians below.

Jobson watches the ritual unfold. For eight hours, Perry hounds Palmer, forcing him to redo a song until the singer’s vocal cords are reduced to broken glass. At one point, Perry yells for Pauline. His wife. She emerges, covered in flour. She’s been making dumplings. Perry wants her to sing a line. After brushing herself down, she obliges. Line delivered, she returns to her dumplings.

“At the time you could sense his genius,” Jobson recounted. “But it was this kind of madness.”

The madness is infectious. A few days later, Jobson returns to the Black Ark. No session gig this time. He cuts a five-track demo of his own. Perry stays up all night producing it.

The Black Ark had claimed another acolyte.

During a brief but glorious period in the 1970s, Perry’s Black Ark generated one of the most distinctive, inimitable sounds of the twentieth century. For a few years, this ramshackle compound in Washington Gardens became the gravitational center of Jamaican popular music. Bob Marley, Max Romeo, and Junior Byles all recorded there. Paul McCartney bent the knee. The Clash attempted to secure their own audience with the king, eventually recording with Perry in London instead.

It was a world made in Perry’s image. His technology was comically unsophisticated. Rivals were upgrading to eight or sixteen-track recorders; Perry settled for a simple four-track. When he needed to rewind tape, he used a screwdriver to reset the counter. “We didn’t have anything professional,” he later said. He didn’t need it. “The sound was in my head and I was going to get down what I hear in my head.” 2

Besides, what need was there for complicated machinery when he had the flesh and blood of the Black Ark itself at his disposal? The studio was his partner, his muse, “like a living thing, a life itself.”3 He created a deep bass sound by burying a microphone under a tree and hitting the trunk. Percussion came from the clanging of garbage pails, from screwdrivers and pliers, from the heel of his foot banging against the bin. He folded the sounds of crying babies, breaking bottles, kitchen utensils, and assorted yard debris into his productions, often mutating them beyond recognition.

It was a “shamanistic” approach to music-making, said Linton Kwesi Johnson, who interviewed Perry in 1977. “A kind of magical act, an act of conjuring up things, whether they be evocative of Africa, judgement, Armageddon, or whatever.”

Perry worked to strengthen the Ark’s connection with those other realms. He conducted spiritual rituals over the machinery. He covered the walls with painted handprints, kung-fu posters, album sleeves and pictures of Haile Selassie. A Bible sat in pride of place, uneasily sharing the room with lewd magazine cutouts of naked women. The equipment itself was caked in ash, candle wax, and fluids, including faecal matter, which Perry would spray to enhance his machinery’s spiritual properties. All of it floated in thick plumes of ganja smoke.

From madness, a method emerged. There was more to Perry than vibes. “He’s a very technical guy,” said singer Earl George. “You can be playing a drum pattern and he say, ‘Play that upside down.’ His way of working is very unique: his rhythms have a different sound, as the mix is totally different from everybody else […] When he mix all the sounds together, you get some way-out kind of sound. You see, Scratch is a genius.”

He wasn’t great with instruments. But he knew exactly what he wanted, and exactly how to get it. “He have a sound that he call the ‘conk’”, said singer William Clarke. “he would take his finger and knock it on your forehead and say, ‘This is what I want to hear, the conk.””

Unlike many producers of his era, Perry wouldn’t just sculpt the recordings after the fact. He produced songs live, riding the mixer during the recording itself. “The musicians they won’t even know what goes on!” he later said, “While the musicians are playing, I am doing the phasing. I take the musician from the earth into space, and bring them back before they could realize, and put them back on the planet earth.”4

By 1976 and 1977, the Black Ark housed a maestro at the peak of his powers. It was during this time that the ‘holy trinity’ of Black Ark recordings was made: Max Romeo’s War Ina Babylon, Junior Murvin’s Police and Thieves, and the Heptones’ Party Time. But even those touchstones pale next to the Congos’ Heart of the Congos, an astonishing record that nearly didn’t exist. Perry had been searching for somewhere to plant a breadfruit tree when he stumbled across Roydel Johnson playing guitar. Perry hadn’t seen Johnson in years, but liked what he heard. He invited him down to the Black Ark. Another musician fell under his spell.

Perhaps he flew too close to the sun. In the late 1970s, Perry began to turn against his creation. He became convinced it was possessed by evil spirits. He scrawled unintelligible symbols on the walls. Whispers spread of him walking through the streets of Kingston, hitting poles with a hammer. The studio slipped into disrepair. In 1979, it burned to the ground. Perry would later claim that he had set the fire himself.

It was the end of an era. Roots reggae was on the way out. The digital pulse of dancehall was on its way in.

Before the Ark died, Wayne Jobson found his way back to it. His five-track demo had been a success while he was in the UK studying for a law degree. Now, he wanted a full album under Perry’s guidance. But something had changed. The Ark’s productive madness had curdled into something harder to harness. Perry began proclaiming that bananas were God, insisting Jobson carry a bunch whenever he was present. He spent hours scrawling a massive X on the wall. The studio itself was decaying, yet Perry refused to buy new equipment until his recently dead car battery healed itself.

The writing was on the wall. Jobson took his album elsewhere.

If you enjoyed this, check out our previous instalments on David Byrne, Salvador Dalí, Tchaikovsky, David Lynch and Alfred Hitchcock.

All quotes and anecdotes in this post are taken from David Katz’s “People Funny Boy: The Genius of Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry (Revised Edition)” unless otherwise indicated. Any errors are mine.

Black Art From The Black Ark; by Lee Perry & Friends

Source unknown.

Black Art From The Black Ark; by Lee Perry & Friends