"I became (and still am) more and more convinced that the important changes in cultural history were actually the product of very large numbers of people and circumstances conspiring to make something new. I call this ‘scenius’ - it means ‘the intelligence and intuition of a whole cultural scene’. It is the communal form of the concept of genius."

— Brian Eno

“I had an extremely slow-dawning insight about creation. That insight is that context largely determines what is written, painted, sculpted, sung, or performed.”

— David Byrne

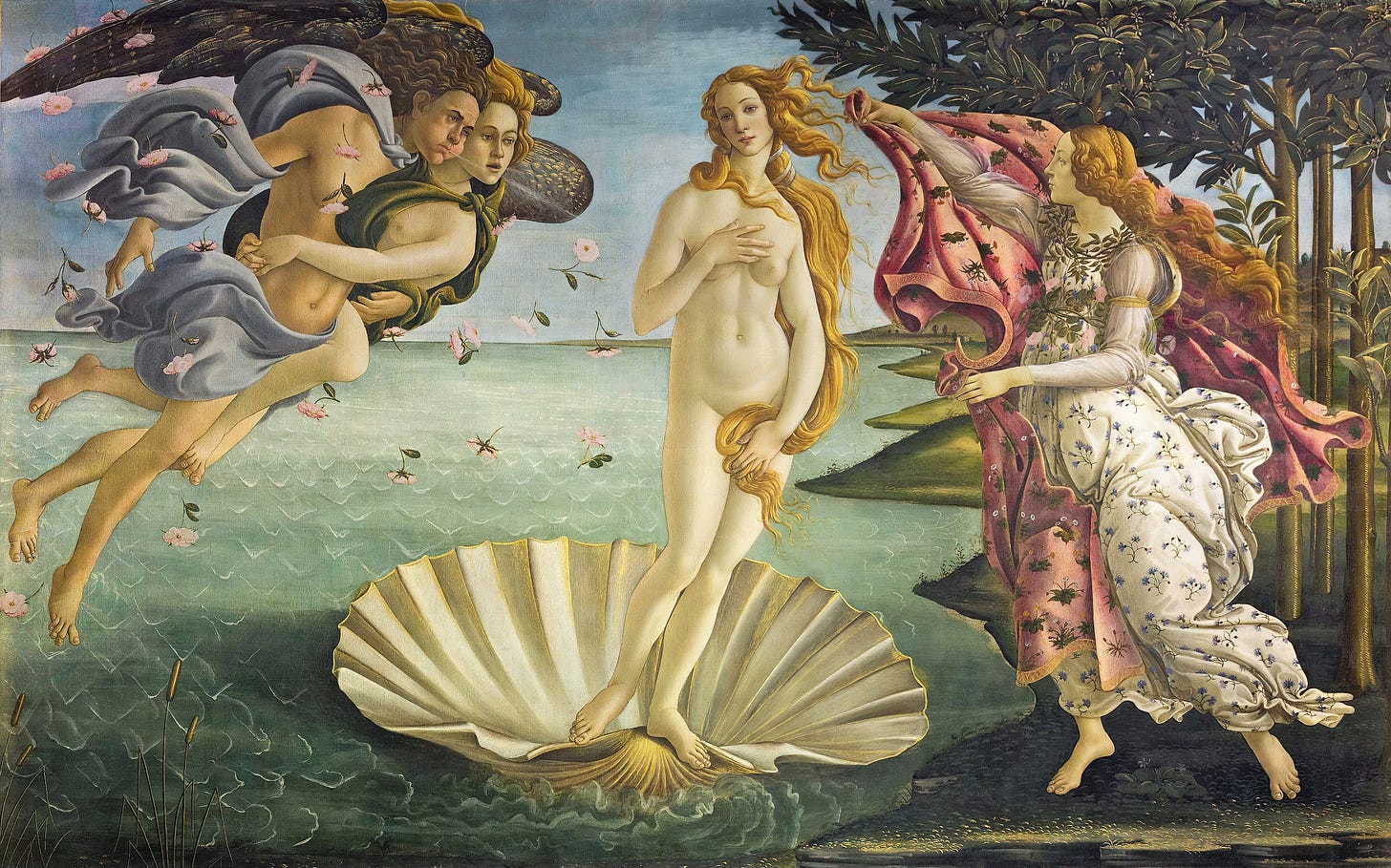

There’s a quiet magnetism to the idea of the scenius, Brian Eno’s oft-cited term for the collective genius generated throughout history by closely knit scenes or communities (canonical examples include Renaissance Florence, Enlightenment Scotland, and c.500 BC Greece).

Perhaps it’s the alluring prospect that we can somehow be responsible for or involved in greatness without having to be great ourselves.

Perhaps it’s the historical romanticism of the idea of close groups of legendary people all operating at the same time and in the same place.

Or maybe it’s the nostalgic appeal of community in the Bowling Alone, Age of the Individual, Always Online era.

Regardless of the reason, once you’re aware of the scenius, it’s hard not to see it everywhere. It's discussed by thinkers like Kevin Kelly, Seth Godin, and Austin Kleon. It’s referenced in your favorite blog posts and podcasts (yes, including Infinite Loops). It’s also, somewhat amusingly, co-opted as a name for an array of professional development, consulting, media, and investing companies:

Although the term “scenius” is deployed with willy-nilly abandon (willy-nillily?), it remains conceptually underdeveloped and underexplored. Kevin Kelly describes scenius as a bottom-up, serendipitous phenomenon that is largely beyond individual control. If true, the term is more descriptive than predictive or prescriptive; a label, but little more. As a social phenomenon rather than a biological or mathematical one, its contours are blurry, its characteristics elusive. Much like pornography, it’s hard to define, but you sure know it when you see it.

Yet, two things seem clear.

Firstly, scenius, whatever it is, appears to be a real phenomenon. From competitive Rubix cube playing to the atomic bomb1, tightly knit social groups bound around a common set of interests and talents have time and again been responsible for unprecedented social, technical, and cultural advancements.

As Austin Kleon has observed, genius, even of the “lone” kind, can often be re-mapped onto a scenius. You can test this now - think of any legendary band, artist, or thinker you admire, and chances are, within five minutes of research, you will be able to identify a specific milieu from which they emerged.2

Secondly, we live in an era in which (1) art and culture are becoming homogenized while politics and social life are becoming polarized, and (2) the forces of The Great Reshuffle are rapidly transforming how we work, live, play, organize, and create. Set against this backdrop, we are seeing a groundswell of new forms of community emerge to try and foster cultural, technical, and artistic progress, from the Network State to New Localism to online salons and writing schools.

These two observations have led us to believe that scenius, a way of conceptualizing the relationship between community and progress, remains just as intriguing a concept as it was when Brian Eno introduced it some 30 years ago. And here’s the fun part - there’s so much more work to be done. As visakan veerasamy once noted: “there are I think less than 100 posts written about this by a range of bloggers.” We are only just scratching the surface.

Below, we've consolidated and summarized some of the key texts defining the concept, starting with Brian Eno and continuing with Kevin Kelly, Austin Kleon, Packy McCormick, and others. In future posts, we'll explore scenius across various domains—from Seattle Grunge to Korean Cinema — documenting its manifestations in film, music, technology, art, philosophy, and beyond.

This series isn’t trying to formulate a Grand Theory of Scenius, much less provide a step-by-step guide for creating it. Consider it instead a humble contribution to the scenius conversation — a hub in which we can gather a steadily accumulating collection of ideas and resources. From here, anyone, anywhere, can start exploring, tinkering, and rabbit-holing, maybe even finding inspiration to start cultivating a scenius of their own.

Finally- we want to hear from YOU. Are there resources we’ve missed? Examples you want us to include? Are there some legendary geniuses whose existence contradicts the idea of scenius?3 Do you think the very concept of scenius is a load of old tosh? Share your thoughts in the comments or by email, and we’ll include valuable contributions in future posts.

For now, on with the Canon!

I. Defining Scenius

Brian Eno’s definition (1996)

“Of course it would be stupid to pretend that everyone’s contribution is therefore equal to every other’s, and I would never claim that. But I want to say that the reality of how culture and ideas evolve is much closer to the one we as pop musicians are liable to accept - of a continuous toing and froing of ideas and imitations and misconstruals, of things becoming thinkable because they are suddenly technically possible, of action and reaction, than the traditional fine-art model which posits an inspired individual sorting it all out for himself and then delivering it unto a largely uncomprehending and ungrateful world.”

The Problem Of Excess Genius; by David Banks (1997)

Banks asks, “Why are some periods and places so astonishingly more productive than the rest?” and argues that traditional explanations tend to be vague and hand-wavey (my favorite: “Gray (1958, 1961) believes that geniuses arrive according to numinously perfect mathematical cycles […] The man is insane.”)

Banks posits a few alternative hypotheses: a substantial military victory in the preceding generation, tight social networks in which great minds could regularly be around one another, personal tutoring, democratic styles of government, and the reinvention of language.

Despite offering these theories, Banks' essay is not trying to answer the question directly. Instead, it is an open-ended challenge to others to answer the question themselves. He ends on an uncertain note: “The problem of excess genius is one of the most important questions I can imagine, but very little progress has been made. It surprises me that essentially no scholarly effort has been directed towards it. I warmly solicit any suggestions from readers that may help me to clarify my own confusion and uncertainty regarding this.”

Scenius, or Communal Genius; by Kevin Kelly (2008)

Although Brian Eno birthed the concept of scenius, Kevin Kelly’s 2008 essay has become its canonical text. Two things stand out:

Kelly’s oft-cited list of factors affecting the development of scenius:

“Mutual appreciation — Risky moves are applauded by the group, subtlety is appreciated, and friendly competition goads the shy. Scenius can be thought of as the best of peer pressure.

Rapid exchange of tools and techniques — As soon as something is invented, it is flaunted and then shared. Ideas flow quickly because they are flowing inside a common language and sensibility.

Network effects of success — When a record is broken, a hit happens, or breakthrough erupts, the success is claimed by the entire scene. This empowers the scene to further success.

Local tolerance for the novelties — The local “outside” does not push back too hard against the transgressions of the scene. The renegades and mavericks are protected by this buffer zone.”

Kelly’s assertion that scenius is a product of serendipity and cannot be intentionally produced. When a scenius does serendipitously emerge: “the best you can do is NOT KILL IT. When it pops up, don’t crush it. When it starts rolling, don’t formalize it. When it sparks, fan it. But don’t move the scenius to better quarters. Try to keep accountants and architects and police and do-gooders away from it. Let it remain inefficient, wasteful, edgy, marginal, in the basement, downtown, in the ‘burbs, in the hotel ballroom, on the fringes, out back.”

If true, the latter assertion would represent a death knell for any attempt to intentionally cultivate scenius. Which leads neatly onto…

Conjuring Scenius; by Packy McCormick (2020)

Friend-of-the-show Packy McCormick’s extended riff on the scenius concept expands and deepens it in a few ways:

Scenius evolves via a three-stage process: starting with a small community of like-minded people, turning into a “micro-scenius” (a “generative community that creates its own novel ways of thinking, doing, or creating”) before finally blossoming into a full-blown, belt-and-braces scenius.

Packy adds four criteria to Kevin Kelly’s abovementioned list of factors:

scenius is often catalyzed by some form of serious crisis (e.g., how Silicon Valley sprouted from World War 2);

intense competition among peers creates a flywheel effect (e.g., Michelangelo vs. da Vinci in 15th-century Florence);

scenius tends to be built around a place-based ritual, i.e., a physical, neutral space in which people can meet and collide ideas (e.g., how Edinburgh’s six hundred taverns functioned as a melting pot for the Scottish Enlightenment);

scenius contains a diversity of thought and experience (e.g., Berry Gordy’s Motown Record Corporation was filled “with white people and black people, men and women. Motown benefited from the diversity of thoughts, experiences, and unique capabilities they each brought, and the doors each could uniquely open.”)

Packy argues that, although the internet has previously not given birth to any scenius due to the constraints of online collaboration, the COVID pandemic could have been the civilizational catalyst we needed to change this (our Great Reshuffle series argues something similar).

Packy pushes back against Kevin Kelly’s idea that scenius cannot be cultivated: “When those conditions are present, as they are today, communities can tap them to mount enough attempts at scenius that a few will stick and change the world. Any one specific attempt may not take, but some will emerge out of the multitude of attempts.”

Sc3nius; by Packy McCormick (2021)

Packy revisits his Conjuring Scenius essay and doubles down on its prediction that COVID will be “the greatest catalyst for progress and creativity in human history.” He evolves the scenius concept in a couple of ways:

Scenius is a product of both exogenous and endogenous factors. Exogenous factors are out of the scene’s control (e.g., an eternal catastrophe), and endogenous factors constitute the scene’s behavior, rituals, and norms (e.g., competition, place-based ritual).

Packy develops a typology of scenius:

Four exogenous ingredients4: human mixing (historical talent clusters were often commercial trading centers), education (e.g., the apprentice-master model in Florence), institutions that encourage risk-taking (e.g., royal support for Shakespeare), & catastrophe; and

Seven endogenous ingredients (each of which were previously identified by him or Kelly): mutual appreciation, rapid exchange of tools & techniques, network effects of success, local tolerance for novelties, competition, place-based ritual, and diversity of thought & experience.

Finding scenius; by Michael Nielsen (2012)

A refreshingly original take on scenius. Challenges the concept in several interesting ways:

There is a difference between, e.g., (1) Renaissance Florence, where a bunch of geniuses seem to have been created *by* Florence, and (2) Los Alamos during WW2, where a bunch of already-existing geniuses were gathered together for a specific purpose. In many cases, we may think that a scenius is the former when it is actually the latter: “I suspect that many other examples which seem superficially like scenius are more like Los Alamos -- great aggregations of talent that will flourish no matter what -- than Florence, where just being in Florence at the right time seemed to help produce much better creative work.”

Conventional scenius explanations would argue that Florence is an example of creative people riffing off each other, thus creating a scenius. An alternative explanation is that Florence, due to external factors such as the Medicis and technological progress, was an unexplored frontier. Like the gold miners who first settled in California, the great artists of Florence got lucky in arriving at the frontier at the right time: “This is what might be called the rich frontier hypothesis of genius: there's a huge advantage to getting in very early as a rich frontier is opening up. There are relatively few other people present initially, and so not only can pioneers stake a major claim, they're often able to remain ahead of the curve for many years or decades, even as the field matures.”

Who participates in the scenius matters. If the scene doesn’t have strong filters, it will be diluted: “Walter Isaacson's recent biography of Steve Jobs shows that one of Jobs's main functions at Apple was as a human barrier, either firing or driving away people who weren't superb at their job. This had many negative consequences, but it's also part of the reason Apple maintained a very good core team, despite being high prestige.”

Nielsen is wary that what may look like causes of a scenius can actually be consequences. He identifies two specific characteristics of scenius: (1) a high density of dedicated people and (2) a large creative frontier relative to the number of people involved.

Nielsen suggests that a test for whether a scenius is, in fact, a scenius, is whether it has “tremendously opened up” the adjacent possible. In other words, has it opened up a huge number of new possibilities that would not have been reachable from the original starting point.

Further notes on scenius; by Austin Kleon (2017)

Kleon differentiates between an “egosystem” and an “ecosystem.” Genius is the former, and scenius is the latter. He argues that human prosperity needs more scenius and less genius:

“Our world is an ecosystem in which our only real chance at survival as a species is cooperation, community, and care, but it’s being lead by people who believe in an egosystem, run on competition, power, and self-interest.”

Maps of scenius; by Austin Kleon (2023)

As well as arguing that we can “re-map” historical geniuses (even reclusive ones) into a scenius, Kleon draws biological parallels with scenius via both viruses and brain neurons:

“innovations, large or small, do not require heroic geniuses any more than your thoughts hinge on a particular neuron. Rather, just as thoughts are an emergent property of neurons firing in our neural networks, innovations arise as an emergent consequence of our species’ psychology applied within our societies and social networks.”

the death and life of great scenius; by Visakan Veerasamy (2021)

Previous Loops guest Visa argues that rivalry between nerds is an underrated factor in the emergence of scenius:

“The real powerful force, I believe, is a bunch of nerds trying to outdo each other. It’s rivalry that drives innovation, IMO, more than prestige, accolades and even financial rewards. It’s Eric Clapton looking at Jimi Hendrix and going What The Fuck.”

II. Building Scenius

Following the Scenius; by Venkatesh Rao (2019)

Another Infinite Loops alumni, Venkatesh Rao, argues that active scenius requires social and idea networking to be the same rather than separate activities: “the key symptom of active scenius is that keeping up with technological change, and with the people driving the change, becomes the same thing.”

Venkatesh also distinguishes between three dimensions of scenius: (1) social (who is doing it), (2) geographical (where are they doing it), and (3) technical (what are they doing).

To participate in a scenius, Venkatesh argues that we need to track at least two, ideally three, of the dimensions mentioned above, provided that one of those two is the what (focusing on the who and where without understanding the what is effectively just posing).

Tracking all three is the golden ticket: “you’ll always be wherever history is being made, and hopefully playing at least a footnote-part in helping make it.”

Networked scenius, private patronage, and the partner state; by Michel Bauwens (2008)

Bauwns quotes Alex Steffen, who argues that scenius does not emerge automatically from the bottom-up (note the contrast with Kelly, who argued that it is a serendipitous phenomenon). Stefen argues that a functioning scene takes hard work and active, top-down cultivation:

“Worse yet is the trend towards (relying on) half-assed citizen media and social networking approaches, projects based on the insane assumption that all that’s needed to court collaborative creativity is a website and a good advertising campaign. This tendency to think that innovative collaboration comes free of cost, bubbling up out the Internet like spring water, betrays a poor understanding of the actual workings of either online collaboration or quality thinking. Most often, when these open/ citizen-media/ online-collaborative approaches work, it’s because a core group in the project provides most of the important input, and usually curates most of the other participants’ input into useful forms. So, frequently, funders’ hopes that they can create transformation on the cheap actually just create a system that appears cheap because it externalizes the cost of expert participation onto the shoulders of others… and when their enthusiasm lags (or they need to get day jobs), the project falters or dies. The examples of failed peer-based social innovation efforts outnumber the successful cases by orders of magnitude.”

III. Everyday Scenius

Scenius; by Austin Kleon (2015)

Kleon hones in on one of the most attractive elements of scenius: its inclusivity. If prolific creativity can be communally produced, then YOU don’t have to be a visionary genius to meaningfully contribute to an emerging, transformative cultural scene:

“Being a valuable part of a scenius is not necessarily about how smart or talented you are, but about what you have to contribute—the ideas you share, the quality of the connections you make, and the conversations you start. If we forget about genius and think more about how we can nurture and contribute to a scenius, we can adjust our own expectations and the expectations of the worlds we want to accept us. We can stop asking what others can do for us, and start asking what we can do for others.”

Scenius, Inspiration, and Invention; by Todd Elkin (2017)

A great example of the malleability of scenius as a conceptual tool. Elkin, an art teacher, explains how his teaching style tries to embody scenius:

“The scenius dynamic also informs my curriculum-design process as well as my daily “teacher moves.” When developing a new curriculum, I think of myself as a member of local and global scenes. My peers are contemporary artists, educators, writers, poets, musicians, designers, researchers in non-art disciplines, and often my students. I’m open to being influenced by these peers, and to the extent that I innovate or even invent new curriculum forms, they rarely emerge from a vacuum.”

Who's in your Scenius?; by Lindsay Johnstone (2024)

A few riffs on scenius that shift it away from the abstract and into the pragmatic:

The concept holds instrumental value even if you’re not actively involved in scene creation: “Ask yourself whether the boldest, most ‘creative’ work happens when you’re at home in your jammies nipping off to hang up a wash between Zoom calls, or when you’re sitting round a table with others. I know which one seems more appealing to me on a dank Glasgow morning, but I also know which will lead to a better flow of ideas, communicated and extrapolated in a common language.”

The creative power of scenius means we should work on our own stuff around others, even if they’re not working on the same thing.

Scenius can be ephemeral, and that’s OK.

Scenius; by Lori Eberly (2014)

Like Elkin and Johnstone, Eberly builds on the idea that our daily lives can be defined by the scenius ethos:

“My personal life is rich with teachers, social workers, and healthcare providers; I am surrounded by people skilled in compassion, service, and kindness. I am also lucky to rub shoulders with folks who live life kinesthetically - personal trainers, coaches, yoga instructors, marathon runners, even my own children; I'm inspired by their playfulness, agility, strength.”

IV. Miscellaneous

The Effectiveness of Unreasonable Small Groups; by Gwern | a database of scenius examples. Some great niche examples in here, including, for example, the previously mentioned competetive rubix cube playing.

Scenius Thread; by Visakan Veerasamy | links to various scenius resources, including some already mentioned here.

Marc Andreessen on Scenius | “I grew up in rural Wisconsin — like, if the job is to get enmeshed into the system, right, into the network, then basically, what you wanna do as an individual is you wanna get yourself into the scene […] You gotta get in the mix, right. And if you’re not willing to get in the mix, it’s not their fault. It’s your fault, right?”

David Senra & Liberty RPF on Infinite Loops | “And to me, what the internet is, it's like a civilizational nervous system for the planet. And it can bring

information from one side of the other and create a distributed scenius…”

Alex Danco on Infinite Loops | “And it's really interesting being in a band and getting to learn how the scene works. Because it is so intricate and multi-layer, different people trying to show off in different ways. And it's like, the people in the bottom of the scene are always trying to move up into the top half and the people at the top half or trying to simultaneously lord over being in the top half, but also try to break away and disassociate themselves with the people in the bottom half of the scene. It's all very interesting. And once you learn how one of these scenes work, you start to see them just really, absolutely everywhere.”

Creativity starts with love and theft; by Callum Flack | “Scenes are funny things. They involve highly concentrated status displays of love objects, and subsequent disagreements on taste (that is often thinly-veiled jealousy, such is the human condition). But just because you're a serious collector and in the scene, doesn't mean you become a creator. There's a very subtle daemon at play where a scene becomes a scenius.”

Under Pressure: David Bowie, Brian Eno and the Genius of a Scenius; by Dr. Michael Wayne | “And often, with the energy that is felt in a scenius, there is a pressure that drives it, you feel under pressure – this pressure is an impulse, the creative impulse of the universe and the creative impulse of emergence, of the new that is emerging.”

Finding your peer group; by Seth Godin | Your peer group “might be the single biggest boost your career can experience.”

More to come!

For me, this is almost unfairly easy— two of the first names that jump to my head, Talking Heads and Martin Scorsese, are umbilically linked to 70s and 80s New York subcultures.

To take one example - did Taylor Swift emerge from a scenius? (It’s fair to say that I am sorely lacking in Swiftie credentials).

The first three of these are inspired by Johah Lehrer’s 2012 Wired article, Cultivating Genius.

Hey there! Scenius is right at the heart of what we do at Futuring Architectures—it’s the mental model behind all our activities. Here’s one of our newsletters, focusing on Scenius: https://sceniusmag.substack.com/