The Future of Food

How the next agricultural revolution will give birth to an infinite harvest

Before we get to food, let’s talk cars.

The latest version of Tesla’s Full Self Driving is too good to believe on hearsay, you have to experience it to understand. One drive isn’t even enough. It requires time spent with the system, observing how it notices and understands when a driver — in another car, on the other side of the intersection — does that quick hand gesture to indicate you should proceed first. Without any input from you, the car understands. This is a level of nuance that we normally don’t expect from computer programs. Consider the variables: a 2-3 ton rolling metal projectile containing human life is being entrusted to a program. It’s not just the lives of the people inside the vehicle, it’s also the lives of people in surrounding vehicles, pedestrians, even property. Compare this to our prohibitions for who can drive such a vehicle. Humans have to age nearly fifteen years before society entrusts them with this level of responsibility — a responsibility that a programmed neural architecture is now handling with shocking ease.

The safety stats are even more impressive: Tesla’s Full Self Driving technology is already safer than a human. Much safer. I speak from experience. I’ve only been driving with FSD for nine months and it has saved me from at least two collisions, one of which I’m fairly sure would have left me with debilitating injuries. But FSD is just one system. The nuances capable here point at a radical reimagining of all systems on Earth that humans depend on. And I can think of one system that is particularly ripe for this kind of innovative disruption. Food.

What was the last meal you ate? Chances are you have no idea where each part of the meal came from. Milk from hundreds of miles away, eggs from a totally different farm, blueberries from Argentina, coffee from Colombia, prosciutto from Italy. For now, let’s just focus on fruits, vegetables, and the complete mechanization of human labor that reshaped civilization. In other words,the industrial revolution. Much of food production today is automated. Sort of. It’s automated, but not in the way a Tesla can navigate Manhattan traffic. The automation of agriculture is more like the subway — a fairly dumb automation. Subways are locked onto rails the same way tractors are rows. We’ve created enormous rolling machines that can harvest a dozen or more rows of a single variety of fruit or vegetable, and most of these rolling machines still require a human at the wheel.

But what happens when we extrapolate the level of dynamic nuance we see in FSD to an industry like agriculture? First, we might ask if there is any need for that. Don’t the giant rolling machines that harvest many rows simultaneously work just fine? Sure, they do what they were built to do. But reaching even this degree of technological leverage required heavy tradeoffs.

Such machines require monocrop farming — many ordered rows of the exact same species. This arrangement has radical downsides. One is soil depletion. With so many of the same species with identical nutrient requirements drawing from the exact same patch of earth, that earth becomes deficient in those very nutrients. Compare this to the Amazon rainforest, which never needs to be fertilized or left fallow. The vast variety of species in a forest creates a give-and-take symbiosis in the soil. What one species takes, the other gives back, and vice versa. But in our farmlands, we have chronically depleted soil — and it’s only getting worse. This destroys the nutrient density of the actual plant that we eat. One quick example: You’d need to eat eight oranges today to get the same amount of Vitamin A your grandparents got from one.. No wonder our health is in crisis...1

Another tradeoff of monocropping is pesticides. What happens when you leave a picnic table full of food outside unattended? Well, the critters and the bugs find it pretty fast. Farming, especially monoculture farming, is no different. What happens when a few bugs whose favorite food is corn find a field of corn? Well, they start eating, then they start multiplying, and that field of food can disappear overnight. Humans, in their infinitely iatrogenic ingenuity, decided that dosing the food with poison would be a good idea. And yes, if we are thinking only about first order effects, it does the job. Any bug that tries to eat the food also ingests a healthy amount of poison and promptly dies, leaving the majority of that field of food untouched. Unfortunately, the world we live in — and the fruitfulness of its future — is determined by second and third and nth order effects. It doesn’t take much cognitive horsepower to spot them here.

Pesticides were invented to kill small bugs and bacteria, but not the plant. The dose makes the poison, right? If it doesn’t kill the plant, then it should be fine for humans. Humans are much bigger. Seems reasonable enough, until you remember that our gut is home to trillions of tiny non-human organisms that belong to the exact same bacterial kingdom being targeted by pesticides. Every year the importance of gut microbiota gains more and more footing, yet we’re eating food laced with a poison designed to kill it. That’s certainly a tradeoff. And given the rise in chronic disease, obesity and other conditions, it certainly makes you wonder.2

But a complete grocery list of the problems with our current food system is not the goal of this essay. We need only a taste of such questionable practices to ask: Is this the best we can do? Where can we go from here?

To get a clearer picture of what’s coming down the pipe, it’s worth looking backwards for a moment. Many centuries ago — perhaps even millennia — a technique of intercropping was developed in Mesoamerica called a ‘milpa’. It’s one of the most sophisticated agricultural systems ever devised. Here’s Charles C. Mann’s description from his landmark book 1491:

A milpa is a field, usually but not always recently cleared, in which farmers plant a dozen crops at once including maize, avocados, multiple varieties of squash and bean, melon, tomatoes, chilis, sweet potato, jicama, amaranth, and mucuna... Milpa crops are nutritionally and environmentally complementary. Maize lacks the amino acids lysine and tryptophan, which the body needs to make proteins and niacin;... Beans have both lysine and tryptophan ... Squashes, for their part, provide an array of vitamins; avocados, fats. The milpa, in the estimation of H. Garrison Wilkes, a maize researcher at the University of Massachusetts in Boston, “is one of the most successful human inventions ever created.”

This food system — the milpa — is what powered the Aztec empire. So why don’t we use it today? It would make the soil richer, our crops nutritionally denser, and humans healthier. Additionally, the variety of crops would make it more resilient against pests wiping out the entire growing effort. So we wouldn’t need pesticides, which would mean our health could (and should) improve across two dimensions: less poison ingested, more nutritious food.

The issue is with our current state of ‘automated’ agriculture. An enormous machine designed to harvest 32 identical rows of corn (The Calmer 3215) can’t do anything with a milpa, except maybe destroy it. A milpa is nuanced and agile; monoculture, blunt and straightforward. Thus, monoculture requires blunt and straightforward machines. And these machines are not cheap. Calmer 3215 corn heads can cost more than $200,000—and that price doesn’t even include the tractor that pushes them! Not to mention the fuel and the manpower required to drive the tractor. Imagine spending nearly a quarter of a million dollars on one piece of equipment and then some hipster teenager walks up to your farmer’s market stall and starts lecturing you about milpas. “Oh yeah, kid? How am I going to harvest 30 acres with a dozen different species all mixed together?” It’s an understandable mindset, but it’s not an innovative one.

Remember, the blessing of monocropping is its bluntness: a single species planted at the exact same time, so those 30 acres of corn become ripe for the picking at the exact same moment. But this is also the curse of monocropping. Farmers have an incredibly narrow window to harvest enormous areas of food. It’s months of waiting, then a mad rush when harvest hits.

With milipas, on the other hand, different species are grown and harvested at different times having different growing times. You might harvest summer squash in July, corn and beans in August, and winter squash in September. The work is spread out, the returns are diversified, and the system is more robust to the whims of weather and pests.With a milpa, basically, there’s less acute stress. If conditions aren’t ideal for the corn this year, other species still make it through. Monocrop farmers live and die by the conditions required for the particular species they have planted. They put all their eggs in one basket and hope that circumstance doesn’t drop it.Milpa farmers, however, have many irons in the fire — if one doesn’t work out, it just becomes fertilizer for the rest.

Hopefully, the path forward is starting to look a little obvious. Unsurprisingly, the same automotive company that figured out how to get cars to drive themselves realized that the same neural architecture behind that breakthrough could be applied to nearly any physical task. So now they’re building a humanoid robot. Tesla aims to ramp up production of their Optimus Robot for about $20,000 each. The economics here are so compelling that the likelihood agriculture doesn’t radically change is close to zero.

Here’s what’s going to happen. One curious farmer is going to realize that for the price of just one Calmer corn head ($200,000+), he can buy ten Optimus robots at $20,000 a pop. This is the Model T moment for agriculture.

A slight detour into the history of car adoption is useful to understand the economics of disruption.

When Henry Ford introduced the Model T in 1908, it wasn’t just novel. It was cost competitive. Operating costs? Two cents per mile, according to Ford Times. And what was the alternative it was poised to replace? Horses. An animal that required daily feed, even when it wasn’t being used. To say nothing of the stabling, medical care, and constant maintenance. Think about it. Imagine feeding your car several times a day, even when it’s just parked for a week. And what would you rather change, a tire or a horseshoe? When Ed Tucker, a stagecoach operator in Michigan, switched from horses to a Model T, it cut his travel time from half a day to 50 minutes. He went from one trip per day to four — quadrupling his profits while eliminating the time and expense of horse care.3

The Model T wasn’t just better. It wasn’t even comparable. The same paradigm shift is about to happen with agriculture. Our current monocrop behemoths are Titanics. They’re huge. They’re expensive. They’re completely lacking in versatility. And they’re headed for a graveyard. Humanoid robots won’t be used for picking 30 acres of corn. They will be used to plant, tend, and harvest an enormously varied and dynamic food forest — dozens of crops, if not hundreds. And the economics of these robots? The upfront costs, maintenance, and power required to operate them? Well, that’s about to turn traditional agriculture upside-down.

Right now, farmers are forced to take big bets. They buy the $200,000 corn harvester, along with millions of dollars worth of other equipment, and pray the sun and rain are in their favor. Tragically, for this and many other reasons, many farmers operate with huge amounts of debt. They run a risky business, riddled with absurd regulations, subsidies, bad incentives, and insidious economic overlords.4 As it stands, traditional farming is like taking all your money and going all in on one stock. As investment portfolio managers love to say, ”Diversify.’ And despite the poor performance of such managers, it amounts to the sage advice of your grandmother. Don’t put all your eggs in one basket. But that’s exactly what farmers are forced to do.

Here’s how it’s going to play out. One enterprising farmer orders an Optimus, figuring it can help with housework. After a while, he’ll ask it for other use cases. The robot accesses the internet, reads this essay, explains my thesis, and makes a suggestion. “After I’m done with the housework, why don’t we start small with a permaculture experiment? Just one acre?” And that’s the first domino. After seeing how cheap and robust it is, the farmer orders a few more robots — and so begins the conversion of his monoculture farm to a complex, year-round, milpa-style permaculture operation.

This first farmer who goes rogue and fully commits to such automated diversification is going to find an entirely different reality on the other side of the switch. No longer is the year divvied into a few enormous purchases of seed and fertilizer in order to reap the benefits with one or two enormous sales of a single crop. Instead, the diversified farmer, now with a robotic army of gardeners, can rely on the sale of dozens and dozens of species, many of which are staggered through the growing season.

The key difference? The hand. That $200,000 corn head can only harvest one species in orderly rows. But just as our own hands enabled our first agricultural revolution and our entire technological flourishing, a robotic hand with a human form factor can harvest literally anything — in any order. From a business standpoint, it makes all the sense in the world. Would you rather try to make back your investment with one risky product? Or would you rather have several dozen products on the market, all with lower costs?

And what about risk? A new bug mutation that renders a pest resilient to pesticides can wipe out an entire crop. With a giant milpa — a food forest — the risk is minimal. So what if one crop gets wiped out? There are several dozen more. Not to mention that many species of plants attract many competing non-plant species, making total crop destruction less likely. The system is robust in the exact ways that our current system is fragile.5 A well-designed food forest also doesn’t need fertilizer, further lowering costs. And the fuel that’s used to run the tractor pushing the Calmer 3215? Not cheap. Robots, on the other hand, are going to get most of their energy from solar panels. After the initial investment, the operating costs for an army of robotic gardeners can become shockingly cheap. (Worth noting: solar panels have now become so cheap that it’s cheaper to build a fence with solar panels than with wood.) And unlike humans, robots don’t need to sleep.And unlike giant tractors, robots can learn.

Imagine, for a moment, that a few hundred thousand acres of farmland in the United States have been converted to milpa-style food forests that are tended, maintained, and harvested by an army of robotic gardeners. All of the data required for the robot to function — the visual input primarily — gets fed to the same system. This robotic army experiments continuously, tracking with extreme accuracy which species do best with which neighbors, at what proximity, and in exactly what conditions: temperature, humidity, altitude, latitude, etc. Any new discoveries can instantly propagate to the rest of the robot army so that every operation with similar conditions immediately benefits.

What happens to the cost of food? Imagine you are that farmer looking at your numbers for the year after investing in a robotic army to tend and harvest a food forest. The new equipment? Much cheaper than the old equipment. The fuel? Free, after that investment in solar panels and batteries (getting cheaper by the month) has been recouped. Factor in the savings from fertilizer and pesticides, neither of which you need anymore. The profit margins are suddenly in a different league.

Substantially lower equipment and operational costs mean an ability to undercut the market. Now this is where things could get a little… weird. Imagine multiple farmers with this setup suddenly engage in price competition. It races to the bottom real quick, because long-term operating costs could end up being very low. (Realize, after a certain scale, robotics will hit an inflection point where they’ll not only repair one another, they’ll assemble all future generations of robots.) At first this sounds like an odd disaster, but think about a minute. Dirt-cheap, high-quality food?

Yes. A solar-powered robotic army of gardeners tending and harvesting hundreds of thousands of acres of food forest will usher in the Solar-Punk utopian dream of extremely cheap, potentially free, definitely highly-nutritious food for all. Sounds fishy. But before succumbing to skepticism, consider oxygen. We need it more than food or water. We die in minutes without it. But do we pay for it? No.Why? The distribution system is perfect. Trees and algae produce and diffuse it throughout the air. Our relationship to oxygen required no analogous agricultural revolution because the manufacturing and distribution systems for it were already perfect. The same was not the case for food, but it could be. With enough solar-powered gardeners tending, harvesting, and transporting, food could become as freely accessible as oxygen.

The future of food as foreseen here doesn’t resize the slices like so many novel socio-economic models do. Instead it grows the pie. By a lot. And this pie is one that we’ll literally eat. It is important to keep in mind,this isn’t going to happen overnight. The process will be gradual, even glacial. But I personally don’t think it’s wise to consider all of this and glibly conclude: “Not in my lifetime!“ The future is no longer a distant dream to be confined to the pages of sci-fi novels. It might be hard to see the future, but that’s only because it’s just around the corner.

So, next time you pull up to a red light while driving, ask yourself: If a car can see that red light and understand it, what’s stopping similar systems from roaming forests of food and stopping to pick a big juicy tomato?

Here are the dismal numbers: between 1950 and 1999, USDA studies of 43 vegetables found calcium content declined 16%, iron by 15%, and vitamin C dropped significantly. Another study tracking 12 vegetables from 1975 to 1997 found even steeper declines: calcium down 27%, iron down 37%, vitamin A down 21%, vitamin C down 30%. Modern wheat varieties (post-1968) contain 19-28% less zinc, copper, and magnesium than older varieties. So, what happens when you are chronically malnourished despite having a full belly?

As for the soil: US farmland loses an average of 4.7 metric tons of topsoil per hectare every year—about 2.1 tons per acre. In the Midwest, estimates run as high as 11 tons per acre annually. Topsoil takes roughly 1,000 years to form one inch. One inch weighs about 160 tons per acre. In other words, every year we lose 13 years’ worth of topsoil in the average field and 69 years’ worth in the Midwest. We could run out of usable topsoil in 60 years. Atrocious, might be the first thought, but imagine if technology gives us a path towards restoring the Earth’s fertility...

The US uses about 1 billion pounds of pesticide every year. That’s about 3 pounds for every person in the country, or about 11 aspirin tablets of pesticide applied to your food every day. Yum. Sure, most of it gets washed off, you might say. Well, 75% of produce still has pesticides after washing. Even worse: many modern pesticides are systemic, meaning, they don’t just sit on the surface of the food, they’re absorbed into the plant’s tissues - they can’t be washed off. Stick that in your salad.

Now get this: 72 pesticides banned in the EU are still used in the US. 17 pesticides banned in Brazil are still used in the US. Even China has banned 11 pesticides that are still used in the US. I’m sure you’ve either heard or experienced the classic anecdote: American goes to Europe, can suddenly tolerate gluten and loses weight while eating baguettes every day. Guess what the US does that Europe doesn’t: the US sprays glyphosate on wheat right before harvest, which accounts for 50% of our dietary exposure. An interesting question in light of this might be: how does glyphosate affect the 35 bacterial species in the human microbiome that metabolize gluten? I’ll let you research that one, but only after sending you on your way with a dark sense of foreboding.

And the poor little bugs. Flying insect biomass is down a whopping 76% in 27 years. Global insect populations are down 40-50%. Insects represent over 80% of Earth’s biodiversity, and they are —well— dropping like flies. Such strong pesticides couldn’t possibly be having a negative effect on your microbiome, certainly no effect on your overall health, right?

Ok, psych, the Model T had a much higher upfront cost! But, the devil is always in the details - although, so is the divine. A Model T in 1909 was $825-850. A horse could be purchased for as low as 10 dollars. 50 if you include a saddle. If you had a buggy, that gets you in the $150-250 range. So how does a technology that’s 4-16 times more expensive replace the horse? Even more troublesome, the annual operating costs were also about the same. The Model T was slightly cheaper with an average of $260/year, all maintenance included. A horse averaged $300/year, all included. So what gives?

Well the cost of a horse is relatively stable. The Model T on the other hand became dramatically cheaper. Between 1911 and 1915 the cost dropped a staggering 44% from $680 to $440. In just another 5 years the cost would approach horse parity and eventually drop below the cost of a horse. In 1908 it took 12.5 hours to build a car. By 1914, Ford’s revolutionary production line concept brought the time-to-build down to 93 minutes. As Ford famously said: “Every time I reduce the charge for our car by one dollar, I get a thousand new buyers.” And all the while the costs associated with a horse remain relatively stable.

But raw cost isn’t the whole picture. The other half is what you can do with the thing you’ve purchased. A horse had about 4-5 good years in an urban setting, and in that time it would take you about 24,000-30,000 miles, at an average speed of about 5-8 mph. The Model T? Ford’s car would last 5-7 years and take you 30,000-50,000 miles at a whopping 40-45 mph with a cruising speed of 30-35 mph. So the Model T was 4-6 times faster, which means the Model T gave you back time - the most valuable resource of all. For nearly identical operating costs, that’s an enormous benefit, but remember, the Model T also eventually got cheaper than a horse and buggy. And horses were dangerous: In 1867 New York, horses caused 4 deaths and 40 pedestrian injuries per week. They could get spooked. Imagine if your car suddenly veered off the road into a ditch if an oncoming driver flipped on their headlights. The horse never stood a chance.

Plus, you know, your car doesn’t shit everywhere. By 1900, New York’s 100,000+ horses were dropping an astonishing 2.5 million pounds of shit on the streets per day. That’s a lot of shit. So how about it? Horse, or car?

Now this is where things get so dark even the sun shies away in shame: In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled in Bowman v. Monsanto that farmers cannot save and replant seeds. This practice of saving and replanting seeds is the definition of agriculture and it’s an innovation that is as old as civilization itself. Since 2013 Monsanto has filed over 100 lawsuits against farmers for seed patent violations, collecting over $20 million. Farmers sign contracts prohibiting seed saving, which forces them to buy new seeds every year. And of course these seeds require specific herbicides. Over half of the global seed market is controlled by three corporations (Monsanto/Bayer, DuPont/Corteva, Syngenta). So farmers have to buy seeds and chemicals every year, and go into debt in order to do so. Farm debt hit $592 billion in 2025. Farm bankruptcies jumped 55% in 2024 (216 filings) and by mid-2025 there were already 361 filings. Government subsidies also play a part here. Corn receives 30.5% of all federal farm subsidies ($3.2 billion annually), which incentivizes monoculture. So the government pays farmers to grow one crop, corporations force them to buy patented seeds and chemical every year, and banks loan them money to buy incredibly expensive equipment. It’s not technically indentured servitude but if a 21st century feudal system was going to look like anything, then look no further. Would you be surprised to learn that the suicide rate among farmers is 3.5 times the general population? So, the next time you find yourself throwing out that half eaten corn cob, think about the dead farmer who couldn’t handle the stress of overdue debt payments. Yum!

In fact, some theorize that the Amazon rainforest may in part be the overgrown remnant of an enormous food forest operation that fed huge populations in South America prior to the arrival of the European diseases that wiped out most of those populations. Whether the Amazon was consciously shaped or not is besides the point: edible species have persisted there for centuries and millennia without pesticides, and this is due in large part to the diversity of species and the way this balances competitive dynamics between the eaters and the eaten. The same is not true for a field of corn, hence pesticides.

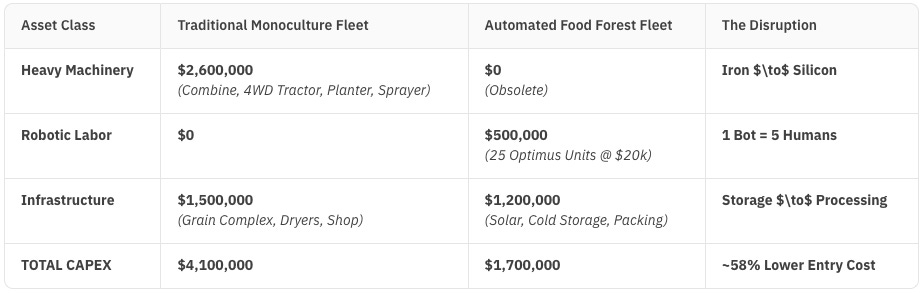

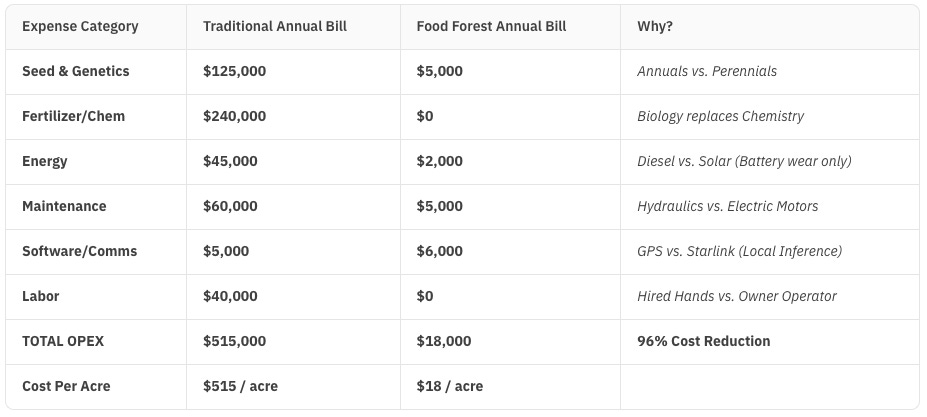

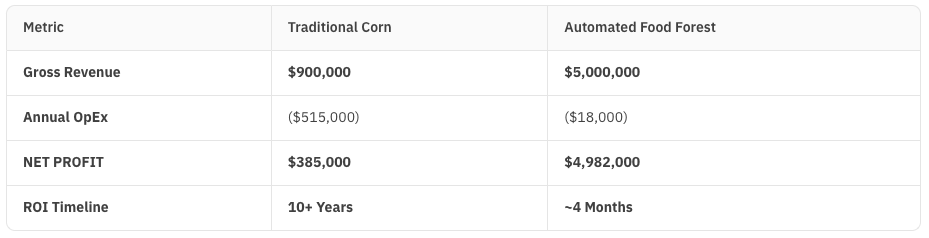

Comparative Economics Methodology: Data assumes a standard 1,000-acre commercial operation.

Traditional Monoculture costs are derived from 2024 University of Illinois crop budgets for high-productivity farmland.

Robot Density & Labor Logic: The allocation of 25 robots is derived from a "First Principles" analysis of available work hours. A human worker is biologically limited to ~1,600 effective hours per year (8-hour shifts, breaks, fatigue, and daylight/sleep restrictions). An Optimus unit, utilizing local inference (no latency) and rapid charging (similar to Tesla’s V4 architecture), is estimated at ~8,000 effective hours per year (22-hour duty cycle, perfect night vision, no fatigue). Therefore, in terms of raw labor availability, 1 Robot $\approx$ 5 Humans. For a 1,000-acre food forest estimated to require ~150,000 annual labor hours, ~19 robots are mathematically required; the model budgets for 25 units to ensure redundancy.

Payback Period (ROI): Calculated as $\frac{\text{Total CapEx}}{\text{Annual Net Profit}}$. The massive disparity (10.6 years vs. ~4 months) illustrates the “Asset Swap”: trading depreciating heavy machinery (high maintenance, fuel, single-use) for robotic labor (low maintenance, electric, multi-use) combined with the significantly higher market value of polyculture produce ($1.00/lb avg) versus commodity corn ($0.08/lb).

Note: Food Forest revenue figures assume a mature ecosystem (Year 3–5). While the robotic hardware pays for itself in 4 months of full production, the biology requires time to establish.

Excellent framing on how intercropping systems like the milpa solve core problems modern ag actively creates.The economics around robot armies versus monoculture machinery is particularly sharp, especially the part about diversifying risk across dozens of crops instead of betting everything on one. What I found compelling is the cascade effect once soil fertility starts compounding instead of depleting,the whole model flips. I've seen permaculture setups where biodiversity alone crushes pest pressure without any chemical interventions. Scaling this with autonomous harvestng could legit crack food scarcity.

Hmm. Fun to read, I guess, in the way it would have been fun to read Tom Swift a generation ago, but pretty silly. Funny the Aztec way of agriculture didn’t catch on. Probably Monsanto sacrificed it.