Welcome to a new series here at the Infinite Loops Substack.

Periodically, eccentric-in-chief Jim O’Shaughnessy will share some of his favourite anecdotes and characters from the book ‘Zanies: The World’s Greatest Eccentrics’ by Jay Robert Nash. New Infinite Loops team member Ed William will then seek to draw some lessons from these strange and wonderful tales.

We hope you enjoy!

The Hoax

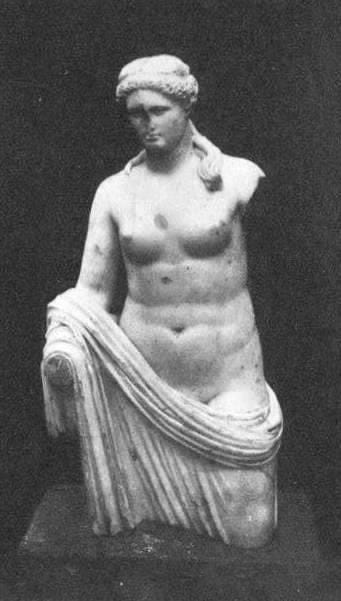

Today’s entry illustrates that we’ve had ‘Deep Fakes’ for a long time. Our story begins in 1938, when a French peasant digging up his turnip patch outside of Saint Étienne in the Loire Province of southern France plowed up what many at first thought was one of the most remarkable art relics in modern history; a Venus which was missing a hand, nose, arms, and legs (pictured below). Art critics flocked to inspect the rare find, pronouncing the statue a lost treasure dating from the Roman invasion of Gaul. ‘Experts’ stated that the Venus was between 1700 and 2500 years old, a genuine artifact of the neo-Attican era.

President Lebrun of France signed a decree that requisitioned the, now named, Venus de Brizet, stipulating that the statue was a national art treasure. Experts agreed that the incredible find had enriched the nation’s cultural history and placed an enormous value on the statue; some said it was priceless.

At the height of this artistic hubbub, a little-known sculptor, Francesco Cremonse, stepped forward to state that he had created the Venus and buried it in the peasant’s turnip patch. The critics responded with uproarious laughter and jeers that gave way to indignant silence as Cremonse produced the statue’s missing nose, hand, arm, and legs, as well as the woman who had served as the model.

The statue was no longer a national treasure. Cremonse’s motive was simple. In his eccentric fashion, he had planned to expose the art critics as inept experts who could easily be duped by anyone with a modicum of talent.

Ed’s Thoughts

Whether he realised it or not, our friend Monsieur Cremonse was tapping into a rich history of hoaxes being used expose the vacuous core of the artistic establishment.

A personal favourite is the story of ‘Pierre Brassau’, a renowned Swedish artist whose startling paintings took a 1964 Göteborg art show by storm. One critic gushed that:

“Pierre Brassau paints with powerful strokes, but also with clear determination. His brush strokes twist with furious fastidiousness. Pierre is an artist who performs with the delicacy of a ballet dancer”.

The catch? Pierre Brassau was in fact a four-year-old chimpanzee called Peter, whose artistic abilities had been ‘employed’ by a Swedish journalist to expose the emperor’s new clothes nature of the avant-garde modernist movement.

Another example is the delightfully named ‘disumbrationism’ movement, a fake art movement which was started single-handedly by an aggrieved academic with no artistic skills to seek revenge on the modernist art community for its dismissal of his wife’s realist paintings.

Fictive Art

So how can we conceptualise this enjoyable catalogue of artistic deception?

The artist Antoinette LaFarge has introduced the concept of ‘fictive art’. She writes:

“A working definition of fictive art might be expansive fictions that are actualized and temporarily secured as factual through the production of evidentiary objects, events, and entities.”

A classic example of fictive art is Norman Daly’s ‘Civilization of Llhuros’, an imaginary civilization which Daly created and subsequently documented via an exhibition of fake artefacts and artwork.

More recently, Iris Häussler’s ‘He Named Her Amber’ was a historical exhibition located in a house where the titular Amber had worked in the 19th century. Of course, it transpired that Amber had never existed: the entire exhibition was a fiction.

So are the stories of Venus de Brizet, Pierre Brassau and the disumbrationism movement examples of fictive art? Potentially. Their use of an artistic hoax to elicit a reaction certainly resembles the work of Häussler and Daly. However, whether they technically fall into the category of fictive art or not, I’m not convinced that artistic inspiration is a sufficient explanation for the actions of our protagonists.

Daly was said to have “no polemic intent” with his fiction – instead it allowed him to emphasise “deception, obscurities and satire, strategies aimed at stimulating audience involvement”. Likewise, Häussler’’s intention was not to trick people, but instead was about “enabling imagination”. In each case the hoax served an open ended, artistic purpose. It was about, in LaFarge’s words, using “the methods of art to offer a path of reflection on the very issues that it embodies in its own structure.”

Something feels qualitatively different between the noble artistic intentions of Daly and Häussler, and those of Cremonse, our Swedish journalist and our aggrieved academic. For each of these individuals, the ultimate intention of the hoax was not to explore, it was to expose. These characters were not driven by inspiration, they were driven by resentment, by disdain. In this sense, their hoaxes served a very narrow, openly aggressive purpose: to delegitimise their opponents.

To truly be able to conceptualise these hoaxes we therefore need to step outside the realms of art and visit the world of psychology.

Status

What explains our protagonists’ aggressive desire to expose the hollowness of the artistic establishment? One answer is that it was simple aestheticism. Perhaps Cremonse hated the preferences of the ivory towered art critics. Our Swedish journalist clearly had little time for the supposed inventions of the avant-garde movement.

But this feels insufficient as an explanation. I think that there was something more fundamental in play.

Recent Infinite Loops guest Will Storr writes the following in his book ‘The Status Game: On Social Position and How We Use It’:

“Life is a game. There is no way to understand the human world without first understanding this. Everyone alive is playing a game who’s hidden rules are built into us and then silently direct our thoughts and emotions and virtually everything else that we do in our behaviour.”

This quote is revelatory. Once we understand that life is one big game for the ultimate prize: status, we can begin to look at human interaction with a fresh perspective.

So what games are being played in Jim’s story (and also in the story of Peter the monkey and the rise of the disumbrationism movement)? Some thoughts:

In carrying out such a brilliant hoax, Cremonse was playing what Will would describe as a ‘dominance game’. It wasn’t sufficient for him to choose to ignore the vacuous pronouncements of the art critics, he had to expose and humiliate them. By doing so, he raised his status at the expense of theirs.

The art critics who blindly sung the praises of the statue were playing status games of their own. By placing themselves as the ones able to recognise and confer artistic merit, they were signalling to the community that they were the ultimate arbiters of value. Their actual opinions of the statue were secondary to the status that was at stake in assessing its integrity.

Alas, we cannot leave this story with our sense of status untouched. How did you feel when you read about these self-important art critics getting their comeuppance? If you are anything like me, you would have felt a sense of smug satisfaction. We love watching other people getting tricked, not only because it is funny, but because it makes us feel superior – we can assume that we would never be so foolish. Here lies the genius of Cremonse and other successful hoaxers. Not only do they raise their own status, but they do it in a way that makes us feel like ours is being raised too.

Very thought-provoking! I like it