It’s fair to say that inspiration was never an issue for Alfred Hitchcock. In his 61-year career, he directed over 50 feature films, defined modern suspense, and hosted 267 episodes of the iconic Alfred Hitchcock Presents.

What fueled his unceasing, relentless creativity? A well-optimized morning routine? A carefully curated information diet?

Nope! Instead, Hitchcock pointed to something a little more unusual.

Immaturity.

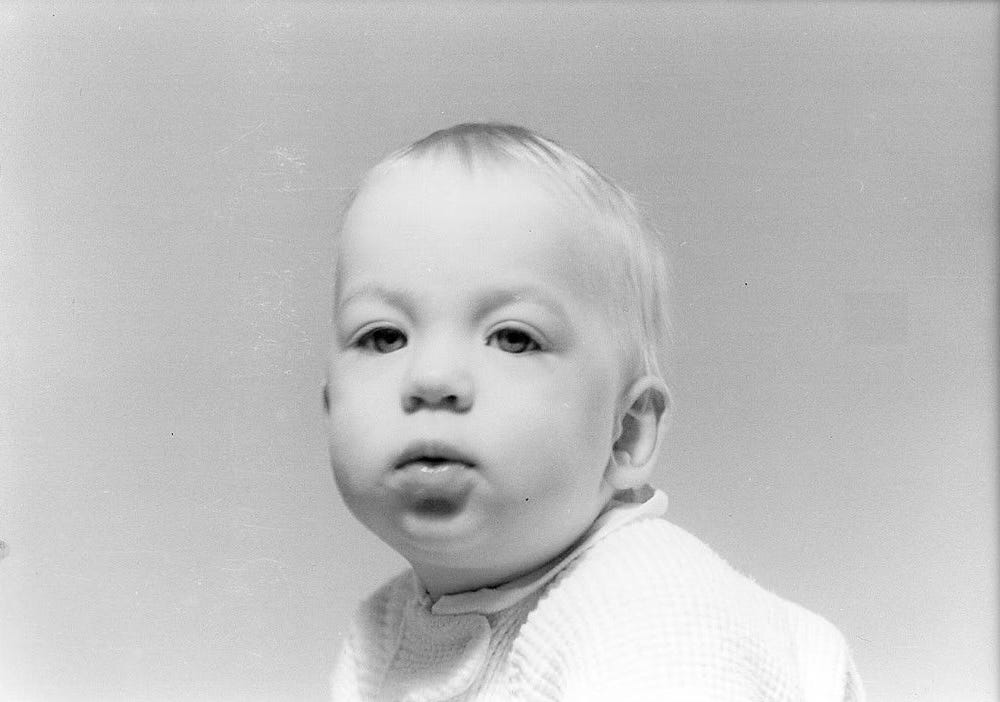

“In a profound sense, Hitchcock thought there was an irreducible part of himself that remained a child all his life,” writes his biographer, Edward White.1 “Not only was it, by his reckoning, the basis of his unusual personality, it was also his source of abundant creativity.”

Hitchcock’s cinema — weighted with fear, suspense and confusion — extended the terrors of his childhood; terrors he chose to channel rather than outgrow.

Throughout his career, Hitchcock regaled interviewers with well-trodden anecdotes constituting what White calls his “genesis myth.”

These anecdotes portray a deeply frightened little boy overwhelmed by the big bad world around him.

A brief stint in a police cell — a ruse set up by his father to instil an instinctive fear of authority. Standing alone in a dark kitchen, submerged by a rising dread that his parents had abandoned him. His mother’s cradle-side cries of “boo,” which he credited for his hard-wired appreciation of the thrill of the scare.

For Hitchcock, the route to creative expression lay within. His films reflected the candlelit, blanket-smothered fears of a wide-eyed little boy.

But his filmography was about more than just childhood terror. Hitchcock was a preternaturally visual filmmaker, one of the best ever at capturing a truth beyond words — Kim Novak framed by the Golden Gate Bridge in Vertigo, the frozen scream of Janet Leigh in Psycho:

To this, he again credited the child’s perspective. White quotes Hitchcock:

“I believe it’s intuitive to visualize, but as we grow up, we lose that intuition […] My mind works more like a baby’s mind does, thinking in pictures.”

In Hitchcock’s telling, it was the mindset of a child that allowed him to resist the pull of intellectualization and tap into pure visual intuition. If you hear a whiff of self-mythology here, you’re not alone. But neither was Hitchcock. “It took me four years to paint like Raphael,” said Picasso several decades earlier. “But a lifetime to paint like a child.”

The structure of Hitchcock’s films — propulsive, provocative, immediate — reflects the impulses of an overactive child; one with little time for the highfalutin philosophizing of his peers. White quotes Russell Maloney who notes that Hitchcock worked “with the mind of an intelligent child who gets angry when his adventure story bogs down midway with talk of love, duty, and other abstractions.”

"What is drama but life with the dull bits cut out?" Hitchcock once famously said. Perhaps childhood is the same — or at least, that’s how we remember it. Hitchcock’s success suggests we’d do well to never outgrow those memories.

The Twelve Lives of Alfred Hitchcock: An Anatomy of the Master of Suspense; by Edward White

Wow, I’m loving this series - whoever is writing them, keep it up!

“I have always felt like Peter Pan. I still feel like Peter Pan. It has been very hard for me to grow up, I'm a victim of the Peter Pan syndrome".

Spielberg on the genesis of ‘Hook’