There’s a quote I heard a long time ago that goes something like this - “India has consistently disappointed both the optimists and the pessimists”.

It is equal parts pithy and profound, and does a somewhat passable job of summarising the multitudes contained in 21st century India. It’s a quote that was brought to life for me numerous times in my conversation with this week’s guest on Infinite Loops - Sajith Pai.

Sajith is a GP at Blume Ventures, one of India’s largest homegrown VC firms. He's known for his prolific writing and sharp frameworks that have become part of Indian startup canon over the past decade.

In 2018, he swapped a long-time career as a media executive for one as a venture capitalist. This changing of lanes, relatively late in his professional life, has given him a refreshingly nuanced perspective on the Indian startup ecosystem (which he’s bestowed with the moniker of ‘Indus Valley’, as a nod to both Silicon Valley as well as the Indus Valley Civilisation, one of the cradles of the ancient world and the ancestral civilisation of the Indian people).

His most compelling insight? That India isn't the monolithic 1.5-billion-person market that many Westerners believe. Instead, it's three distinct "countries" hiding in plain sight. There's India One: 120 million affluent, English-speaking urbanites (think the population of Germany) who love their iPhones and Starbucks. Then comes India Two: 300 million aspiring middle-class citizens who inhabit the digital economy but not yet the consumption economy. Finally, there's India Three: a massive population with a similar demographic profile to Sub-Saharan Africa, that’s still waiting for its invitation to join India’s bright future.

‘India 1-2-3’ is one amongst many pearls of wisdom that Sajith gifted me over our conversation, that also touched on India as a "digital welfare state", India as a ‘low trust society’; the emergence of a new class of ‘Indo-Anglians’; how cultural nuances in India shape everything from app design to payment systems; and much, much more.

Whether you're an investor, founder, or just curious about where the next decade of innovation might come from, this conversation is your crash course to understanding India in the 21st century. Sajith likes to say that ‘India is not for beginners’. Well, if you are a beginner on India, this week you’re in luck.

As always, if you like what you hear/read, please leave a comment or drop us a review on your provider of choice. In the meantime, here’s a sizzle reel to get things started:

Episode Links

Here’s a link to the full episode on our Youtube channel.

If you’ve only got 5 minutes to spare today, here are some of my favourite bits from Sajith’s writing over the years:

Narrative Capital

Narrative Capital is my term for a trend that has accelerated lately in venture capital; one where writers / podcasters / media creators purveying tech and startup content have raised funds / vehicles to invest in startups. Effectively, they are leveraging their large and growing fanbase of followers and consumers to launch an investment vehicle.

Narrative Capitalists in particular have an unfair access advantage as a result of their distribution power. Their media properties act as bat signals attracting founders of all strains to their doors. Even if founders don’t reach out, Narrative Capitalists are likely to hear earlier about early stage investments given their networking and connects, and can also reach out to founders and get into these deals.

‘Exhaust Fumes’, or, Understanding Startup Valuations

VCs found that the techniques that public market investors used couldn’t hold for younger, fast-growing companies with unpredictable revenue. Through long years of iteration, they came with the practice or protocol of playing long-term multiparty staging games to take the company from idea to IPO. It wasn’t invented by one person or one firm. Rather this evolved like markets do, or cities. Think of it as evolution applied to markets. I personally see these long-term multiparty staging games as one of the great financial innovations of the 20th century, on par with say, credit cards, or even microfinance.

Nosumer Media

Thinking of a media category I want to call 'Nosumer Media' (nosumer as short for no consumer). These could be books, podcasts, apps etc. They are created not for consumption as much as for the benefits from creating, or the pleasure of creating accruing to the creator.

Nosumer media creators are aware that it their creations are unlikely to be consumed (in large numbers), and have no overwhelming desire to even see consumption grow for it.

Why would nosumer creators spend time on such media? Well, I see 3 possible benefits for nosumer media creators

· signalling of some skill possessed by the creator

· learnings accruing to creator from the creation process

· meeting interesting, useful or powerful people during the creation process

India1, Avocado Startups and Product-Market Fit

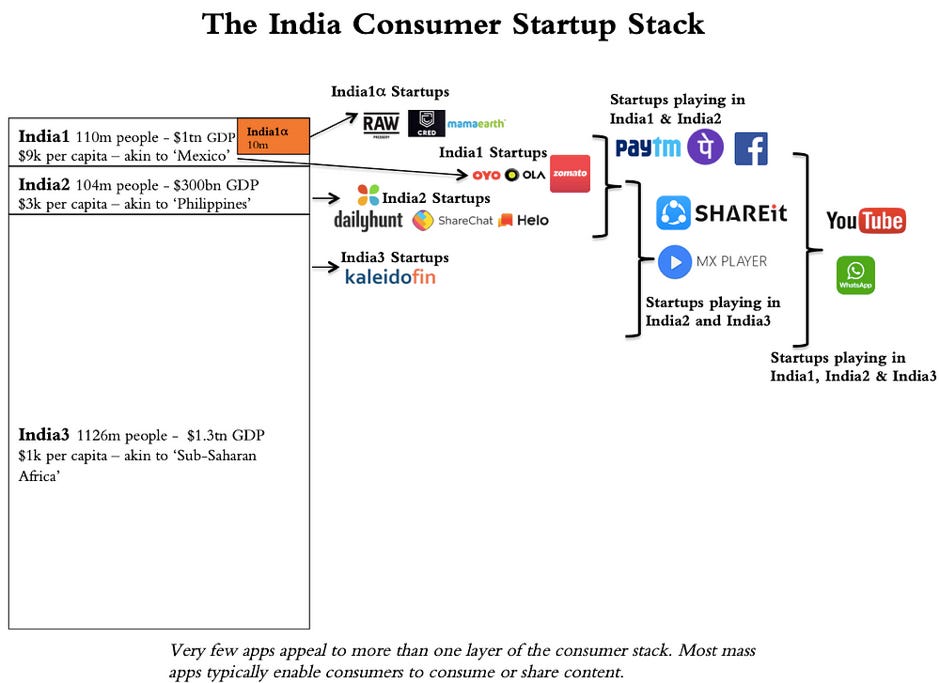

India can be understood as a four-tier consumer stack

A good way to see India is thus as a four-tier market, with each tier being able to support a set of native startups, which struggle to expand beyond their market. Each market has its distinct audience profile, pricing sensitivity, cultural attributes and competitive dynamics. Product market fit (PMF hereafter) in one market doesn’t automatically translate to the possibility of a fit in another. If anything product market fit in one market makes it tougher to succeed in another. There are just a handful of products, typically with universal uses cases (Youtube, Whatsapp, Flipkart etc) that have succeeded in both India1 and India2.

Here is a graphic that illustrates the India consumer stack and the startups that are native to each tier.

India2, English Tax and Building for the Next Billion Users

Let us move on to ‘English tax’. What exactly is this ‘English tax’? I define it as using English language and branding on and around the product to make its usage intimidating for non-English speakers. It may not be intentional but it nonetheless creates discomfort for non-English speakers in trial and usage of the product.

The Indian menu doesn’t accommodate any Indian language. Exclusive English text and the overall design / aesthetics communicate the exclusive and even exclusionary nature of the place. It intimidates an affluent but non-english speaker. Imagine a rich businessman from Satara or Meerut who walks in to a Pune or Delhi Starbucks. This heavy English tax discourages him from ordering a coffee there. Contrast it with a 5-star hotel, which is an even more expensive space but with much lesser English tax — less English signages, lots of servile staff — making it far more palatable for the non-English speaking affluent customer. Of course, the fact that 5-star hotels also cater to international tourists who don’t speak English also helps in creating a space with lower English tax.

What is bad enough offline — a product with a heavy ‘English tax’ — is even worse online.

Say Hello to India’s Newest and Fastest-Growing Caste

I have been looking for a term, an acronym or a phrase that describes these families who speak English predominantly at home. These constitute an influential demographic, or rather a psychographic, in India — affluent, urban, highly educated, usually in intercaste or inter-religious unions. I propose to call them Indo-Anglians[1].

Indo-Anglians

Unlike Anglo-Indians, the original English-speaking community in India, who were Christians, Indo-Anglians comprise all religions, though Hindus dominate. Indo-Anglians are also a highly urban lot; concentrated in the top 7 large cities of India (Mumbai, Delhi, Bangalore, Chennai, Pune, Hyderabad and Kolkata) with a smattering across the smaller towns in the hills and in Goa.

IAs are a paradox. They are both India’s most visible and yet invisible class. I use the latter phrase in the context of their emergence as a distinct category in Indian society, yet one which is not apparent to most. They get lumped amongst the elite and are commonly described as the English-speaking elite class. Yet, as we know not all the elite or affluent classes speak English. And there are many IAs who are not necessarily affluent in the strict sense of the term. Increasingly they are emerging as a cultural class or caste, with their own distinct and evolving set of preferences, behaviours, concerns and needs.

Reflections on Strategy

Strategy is amongst the most ill-used terms in business. Its ill-use is, if anything, even more pronounced in the startup world. There are multiple reasons for that. This essay won’t cover those reasons; that is for another time. Instead, this essay will suggest a universal definition for strategy, and relate it to the startup landscape. I will also share how strategy interacts with the concept of culture, another ill-used term. The objective, then, of this piece is to create a common vocabulary around these topics, so we can start building on them, instead of constantly debating their meaning.

Per me, strategy is a set of interconnected choices, including intentional tradeoffs, that reinforce each other to give you a competitive advantage (relative to your peers) in the marketplace. Now, while this phrasing is distinctive, the concept of strategy as choices isn’t entirely unique or mine. I have adapted it from the definition suggested by Roger Martin and A.G. Lafley in their book ‘Playing to Win’, which to my mind is the best book I have read on strategy.

The choices that you make in arriving at your strategy are primarily around two elements.

Where do you play?

How do you win?

TAM: Notes & Thoughts

TAM is the carpet under which the lazy VC buries his no’s.

If you are a founder and get a pass from a VC who cites low TAM (Total Addressable Market) as a reason for passing, then be rest assured that in nine out of ten cases, that is not the real reason. The real reason most often is that they have something better than you, something that they think is likely to grow faster and bigger than your startup.

Transcript

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

Hi, I'm Jim O'Shaughnessy and welcome to Infinite Loops. Sometimes we get caught up in what feel like infinite loops when trying to figure things out. Markets go up and down, research is presented and then refuted, and we find ourselves right back where we started. The goal of this podcast is to learn how we can reset our thinking on issues that hopefully leaves us with a better understanding as to why we think the way we think and how we might be able to change that to avoid going in infinite loops of thought.

We hope to offer our listeners a fresh perspective on a variety of issues and look at them through a multifaceted lens — including history, philosophy, art, science, linguistics, and yes, also through quantitative analysis. And through these discussions help you not only become a better investor, but also become a more nuanced thinker. With each episode we hope to bring you along with us as we learn together. Thanks for joining us, now please enjoy this episode of Infinite Loops.

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

Well, hello everyone. It's Jim O'Shaughnessy with yet another Infinite Loops. My guest today, Sajith Pai, is one of the most respected people in the Indian tech industry. He's a GP at Blume VC and he's also a very prolific writer. I've read much of what he's written. He's a wonderful writer. And what I love about it is the transition Sajith from two decades in media entertainment and then staking your claim, I think it was in 2018 by joining Blume VC. First off, welcome.

Sajith Pai:

Thank you, Jim. It's a pleasure and it's an honor.

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

And if you wouldn't mind, one of the things that I have been learning a lot about that I'm sure that many of our listeners and viewers don't know too much about is India is seen by many American VCs as this great untapped country with 1.5 billion people, but we see it a bit as a monolith, and at least you've disabused me of those notions and it would be great if you could help our listeners and viewers understand it's not that at all. You've said it's three, maybe four, different countries and that you really need to understand. If you wouldn't mind walking us through a 101 on the Indian opportunity and many of the misconceptions Westerners have about it.

Sajith Pai:

I'd be happy to. A lot of folks outside see India as this large, like you rightly said, 1.4, 1.5 billion population country with a rising middle class. And because a lot of, I would say, folks in the west interact with very smart Indians and especially if you're in Silicon Valley, Indians are a substantial portion. And even in US corporate and as well as British corporates are full of very successful Indians, so typically the notion is that there are a lot of people like them in India, but when you actually unpack the data, you find that that kind of population, highly educated, affluent, well-earning is actually a very small portion of the Indian population. I look at India as four countries, but really three of them are the ones I think it's best understood as. It's a pyramid. India one, India two and India three. India one is the smallest market, and the fourth country is really a subset of India one, which is an extremely rarefied set, which I'll not talk about.

Let's go back to the three countries. India one, India two, and India three. India one is about 30 million households, but 120 million people, but nine to 10% of the overall Indian population and accounts are about $15,000 per capita income. And they're the ones, for example, buying Apple phones, having Starbucks coffee, offices of franchise in India or Dunkin Donuts, buying Samsonite suitcases and what have you. A lot of people think this is a majority of the Indian population, but it's actually just about nine, 10%. But the fact is because they're 120 million people, it's still significant. That's bigger than Germany, for instance. That's bigger than the UK. That's an interesting paradox of India that India one is just about 9% of India, but it's still larger than many countries. India two is a second nation, and that is really aspiring India. There are about 70 million households, 300 million people, they can use internet, but they can't consume.

They users, not consumers. And they account for about $3,000 per capita income more like the Philippines, but Philippines population is about a hundred million. It's like Indonesia with the per capita income of Philippines. India one is like a Mexico. You think of it as a Mexico sized country. And India three is really beyond the pale. They're completely locked out of the economic markets, they're not making too much money.

Thousand dollars per capita income, really struggling to buy, no disposable income and so on. Really these are the three nations, and I think what western companies or any company outside India needs to keep in mind is there are not too many products that appeal to the entire Indian populace. Yes, there are companies like Unilever, Procter and Gamble, more Unilever, and there are a few companies which have products that cater to the entire 1.4 billion people, but really most products really appeal to 30 million households, 120 million people. And if it can appeal to India two, then it's really a big product. That is the three nations and the piecing apart of this, I want to take a pause here and let you come back into the conversation.

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

Thank you. And how do you navigate between these three countries? Do you aim at that tier one or are you looking for founders who you think might be able to go into country two and ultimately country three?

Sajith Pai:

I think all of us in venture, we're really launching I would say... Most consumer products have really kept India three out of our calculations. It's a very large country, 1.2 billion people, or 1 billion people, but it's really outside of our concentration set. Now, one thing to keep in mind is it is not like India one is concentrated in a few cities and India one is in certain regions, it's spread across India. A good way to understand this, if India is water or milk and India one is the cream that spread across. It's concentrated in a few regions, but there's no one part where people talk about Italy and say southern Italy versus northern Italy. Northern Italy is far more prosperous, nothing like that in India. There are some trends where the southern and western parts are a little more richer but nothing definitive but it's spread across, and all of us really keep India one and two in mind.

And we are lucky if the product can also appeal to India two. Very few products appeal to India one and India two. That's because the hooks that are needed to grab onto the landmass of India one are not sufficient or are not relevant to the hook to grab onto the landmass of India two. What I mean is India one speaks a lot of English, very comfortable with what's happening in the US consumption patterns. And I like to think of this metaphor that India one is a 51st state of the US really. They're watching Suits or Friends and what have you, they're really consuming US culture. But India two is not native English speakers. They can see English, some of them can understand English, but they're largely vernacular language speakers. While they can use the English internet, they're not native and they don't leverage it well.

Some of them have started using it for learning, some of them use it for shopping, etc. But they're not native users. India one is very used to clicking on colored rectangles on flat glass screens and buying, but India two likes to use voice. And increasingly a lot of apps have started giving back using the voice interface. And it'd be interesting if AI in the next few years uses voice interface to help make the internet palatable for India two. This is the lay of the land when it comes to venture-funded startup. Very largely focused on India one.

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

And we have direct experience with that in one of our verticals, Infinite Books. On the audiobook, we are looking to be able to translate it into the very many languages spoken in India, and the AI is getting better and better and better at that, so we think it'll be an interesting experiment, at least. By the way, we're doing it entirely experimentally. We don't have any preconceived notions about how that might or might not work. But you've also written elsewhere that India is a low trust society, and are there specific things that you look for? First off, this is a two part question. In the country one that is very comfortable with US culture, etc, is that still a low trust cohort or are they more like the United States in their trust? And then the second question would be how do you build apps that work and appeal in a low trust society?

Sajith Pai:

Yeah, I think that India is a low trust country. There are parts of India, the startup ecosystem, which is really the venture ecosystem is a high trust market, so there are parts of it that are very similar to how it would work in the US. I think the venture ecosystem here is very highly evolved, and that's a high trust, so parts of the market where there are a lot of American banks that are operating or even Indian companies, so concentrated in Bombay, some parts of other cities like Bangalore and some parts of Delhi would be high trust. But on an average, even India one would be I won't say low trust, but lower on the trust levels than I would say western countries. And a lot of it has to do with culture and the fact that end of the day we are a $2,600 per capita income country.

We are 140th on per capita income, and it's only some parts of India which really have anything about 10, $15,000. A lot of that to me itself through the contrasting. With regards to your second question, how do you build products which are high trust? Very interesting, and I'll give you an example of a particular feature which is somewhat unique to India and the challenges it creates. In US, if you want to buy a product from Amazon, Amazon has one click shopping. In India, it doesn't work. I literally have to do six, seven clicks because the Reserve Bank of India, RBI, which is very powerful, which is one of the few institutions like the Fed, but much more trusted, they said a lot of customers are accidentally paying because Amazon made it one click and could pay. No, we want more friction in buying.

Literally have to do multiple clicks. Then there is an OTP that I get, it's called a one-time password, which comes on my phone. And not only do I have to put my CVV, sometimes I have to put it each time or to give special permission, then the OTP comes, so there's a lot of friction in buying and it takes me five, six clicks. Whereas when I'm in the US, everything is designed maybe to just separate money from me in an instant. But in India, there's so much friction, so that is one example for India one even. For India two or even parts of India one, e-commerce is a good example. We have something called cash on delivery. Now this interesting. US you have to pre-pay for anything you want at your house or whatever. In India, you can opt for cash on delivery.

Now what it means is I do not believe that what you're sending me is the right thing. I want to see it, I want to make sure it is, and then I'll pay. Cash on delivery still is a majority of Indian e-commerce and factors people do pay digitally, but they want to see the product in their hands. Now, this is an indicator of what a low trust economy has engendered. The fact also is that our addresses are very hard to make out. They're hard to pass.

They're as simple as US addresses. 1320 Maple Drive zip code. They're half a mile long, and they give you interesting things like, "Come behind the temple, give me a shout, and someone will come." And it's a fourth door with this. One of the Indian apps, Swiggy, even has an option for photographing your door and adding it so that people who are delivering can see the door. This is interesting. This is not related to trust as much, but so much as what it means is aligned with cash on delivery, allied with the fact that addresses are hard to pass and et cetera, we have return rates, which are very high. Some of our apparel companies which do fashion e-commerce, have return rates as high as 40%. It's a nightmare to deal with because it vitiates a unit economics, so I've given you a lot of variety, but I thought two examples of what low trust mean at India one and India two.

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

As I listened to your response, I can't help but think that both of those were problems in the United States way earlier. Cash on delivery, COD, was very popular in the United States as we were emerging as a more unified country because, as you probably know, the states have their own constitutions and they have their own rules and regulations and all of that. And most things were set COD because in that regard we were low trust.

And then the friction on the one-click payment, same thing happened here when the internet started to dominate. And I think it's probably an apocryphal story, but it illustrates the point. It was really the Beanie Baby phenomenon in the United States that got people willing to put their credit card on eBay. Most people, when Amazon was brand... I was a real super earlier adopter of the internet, and I'm a journal keeper too, and I just found something from the mid-nineties where it says, "I don't know if I'm ever going to put my credit card on the internet." And then of course, we became accustomed to it. Do you see similar things progressing that way in India as well?

Sajith Pai:

I do. I think over the last, I would say 20 years, twenty-plus years, 30 years. If you take '94 as the early wave of internet in India, I would say yes, I've started seeing this trend towards more trust, less of friction, more people willing to use credit cards or at least digital payments. Certainly in the right direction, but I would say a lot of this is much faster in India one, a little less faster in India two and non-existent in India three.

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

And I have been very bullish on India, Indian people. Now I'm learning, I'm probably profiling that India one, but highly educated, incredible work. We have a joke at OSV that if an Indian CEO gets installed, then yes. We view it very positively. But as I listen, it seems to me that penetration into country two and country three is going to be a very long adoption curve. And what are your thoughts on how that might happen? I could probably understand how you penetrate the aspiring country, number two, that's just below that 30 million figure you gave for the top one. Do you ever see it getting and permeating the third level?

Sajith Pai:

Yeah. India one has about 30 million...

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

The third level?

Sajith Pai:

Yeah. So India One has about 30 million households and 120 million people.

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

120 million?

Sajith Pai:

India Two is about 70 million households and about 300 million people. I would say that I'm very hopeful of India Two much more. Well, for one, the per capita income is around $3,000. And typically they have low but rising percentage of their earnings as disposable income. And typically around four to $6,000, the disposable income becomes material enough to start influencing the Indian consumer market. And at that point we'll start seeing them becoming a force. What is interesting is that there are people, there are companies which have been able to successfully sell into India too. Some of them are startups, some of them are not necessarily startups in the truest sense, but they're really larger companies launching brands. And one successful company is called Zudio, Z-U-D-I-O. It is from one of India's largest conglomerates, the Tata group, the highly respected Tata group, everything from salt to software, they run airplanes as well.

So they launched, one of their companies launched this brand called Zudio. Effectively it is like Indian Zara H&M, but much lower priced, less than $10 typically. And basically what they did was they worked backwards. They said, "This is the price I want to kind of offer, and this is the margin that I'm comfortable with, hence this is what I need to manufacture it at." They gave a large amount of volume to their suppliers and they were able to get goods at much lower prices. The markups were lower and they sold the product at lower prices and they've been extremely successful. So it's kind of said that Indian consumers are not low price, but they're high value more than low price. And that has turned out to be true.

So second, when it comes to, for example, India's a big market for two wheelers. So there have been, for example, companies which have ... there's a company called Hero Group. They earlier had a joint venture with Hero Honda, but now they cannot separate so Hero Group. So they have a very successful two-wheeler brand, which is very popular in India Two. And a lot of it has to do with fuel efficiency. So they basically said, "We will do what it takes." And they created this four stroke engine. So there's less power, but it gives you tremendous mileage and that really matters in India. So these are two examples and there are many more of companies really working backwards from the price that they have to sell at making sure that the product has features which are relevant for India Two and being able to provide that value. And they've done very well.

There's this gentleman, C.K. Prahalad, not so well known now, but he's passed away. He was an American academic, he was at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He wrote this book called The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid where he talked about how Indian companies can actually sell into India Three. With deep respect to Mr. Prahalad, I think India Three is a little tough. I guess you could, if you're selling products which are like consumer staples, maybe salt or grain or something like that. And another mode that's worked well is to do what's called sachetization, which is really the challenge of making big packs, like you go to Costco and you see these jumbo packs, they won't work in India. You need much smaller, so sachets, because Indians don't have very high income at one go. And very few Indians are part of the formal economy.

Out of the 1.4 billion people, about 600 million people in the labor force, out of which about barely 10% are in the formal economy, which means they get regular income every month and stuff like that. The blue collar population is about one third of this, and the white collar is about two thirds of this. So if you ask me, a lot of these factors also play itself in this trend towards sachetization because when you don't have regular income, you're not able to save towards a lot of things and you are very careful about what you're going to spend it on.

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

And that brings to mind the stat that kind of blew my mind, which is only 1.5% of the total population in India pays an income tax.

Sajith Pai:

So worth noting is, and this is how our two countries have evolved. The US a very local ... the local municipality in the states have a lot of power. So the center, the union has power that is not bequeathed to the states. So India is other way around. The states have power that's not bequeathed to the union. So union is very powerful in India. And that's just the way we've evolved because we basically adopted whatever practices the British had laid down. And the British, because they governed India as a colony, they had a very strong center. And so we just took over from that. And what's worth noting is unlike the US, we have very few local taxes. I do not pay local taxes, Jim, I only pay the income tax and I pay the goods and service tax, which is an indirect tax. But the fact is there are very few Indians paying that.

And I think over the last few years, and there's a very different discussion and I probably shouldn't go there. There's also been a desire by the Indian state to not expand the tax base, the direct tax base. So there's a saying right in the US, no taxation without representation. It's a very important saying in the history of the United States. So in many ways, I think the powerful Indian state goes by the philosophy of no taxation, no representation. So what it means is that if you are not paying tax, then you do not have the right to ask for a lot of things. So the center is not held accountable for a lot of things. What has happened over the last many decades is the Indian elite has sort of segregated themselves from participating in public goods.

So the elite of India live in large gated complexes today, which is sort of the equivalent of the white suburbs in the US. So not all the gated complexes are in the suburbs in India, some of them are in the big middle of the cities, but they large gated complexes, they have security, they drive large cars, and there's a trend towards richer households buying more and more cars. While public transport is used, not enough public transport is used. There is a saying in the West that rich countries one where even millionaires and billionaires travel by public transport. It's not so true in India. So kind of a roundabout way, but it sort of this 1.5% or 22 million Indians paying all of the tax has many implications and not all are necessarily healthy implications.

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

Do you think that that is somehow a remnant of the caste system in India? Is that still influencing the way things are going or not?

Sajith Pai:

Not this specific one, but I would say that if you take the Indian caste system ... so India, unlike the UK where there's a class system, yeah, the caste matters far more and it is not going to be completely. So I would expect it to come down every year and it is reducing. In large cities, it's not as important. But then again, as a member of ... I'm a privileged member of the upper caste, so I won't see it. It's hard for me to see the caste. Much like, for example, if you're a member of the minority in the US, you will encounter far more challenges, which for example, a white American will not encounter. So I may not see it as much. I would say it's come down. There is a strong correlation with income and I would say caste. It is not decisive. There are reasonably large, but a reasonable number of lower castes who have done well or middle castes have done well. But increasingly, I think a majority of the people who've done well economically well off are, I would say, certainly the upper castes. But the tax, so naturally that has an implication in who pays the tax. So that's the way I would put it.

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

Some of my younger colleagues at O’Shaughnessy Ventures who are working from India and are Indians obviously often joke that the largest variable whether India can be the powerhouse of the 21st century is the government. And they say that to me often enough every time I ask a question like, "Well, why isn't this happening, this happening, this happening?" And then the refrain from them always is, "Look, you're right. We've got all of those things that you're mentioning, highly educated, highly motivated, capital formation is VCs like yourself," but they're like, "The government is our greatest exogenous risk here." What do you think about that idea?

Sajith Pai:

To give credit to the government, they do understand that if they don't reform India, they're sitting on a time bomb because this is a country where there's a large number of people who are less economically well off. Unemployment is reasonably high. So to their credit, all governments, especially this government, has been very proactive in, I would say, investing, for example, where it comes to roads, railways. Infrastructure for instance, has improved dramatically. That said, I would say there are two areas where I would say we should see a little more intervention. The first would be the tax one. I think the Indian taxman can be very temperamental. For example, they can come back and say, " You owe us money for the last 10 years, and there's no statute of limitation there." And that does create challenges.

The second is to do with interpretation of laws. And I would say there are enough examples of sectors where the certain laws hobbled the growth of the sector. Now things are changing, but for a long time, India's drones had to be within line of sight. So they couldn't be used in agriculture, they couldn't be used for many things. You had to get a lot of permission. So as a result, the biggest use case for drones was weddings. And because Indian weddings are ... they talk about big fat Greek weddings. Indian weddings are boy, oh boy, they're bigger and fatter. And you had this trend where every wedding had a drone going up, shooting it from multiple angles, etc. So yeah, so that's an example of how law hobbled the growth of the drone sector. Now things are changing. So I think these two are areas where I think we need to see the Indian state ease up a little.

But otherwise, I think there they've been fairly open to the idea that they have to invest. They can't stand in the way of growth. The other minor risk, and this not so much for Indian companies, but for I would say global companies, is that there is, and this not only India, there is a sort of economic nationalism that is rising. And what that means is the Indian state wants more control. We are seeing some of this in Brazil as we saw it with X/Twitter being shut down by the Brazilian Supreme Court. And there is a case that is slowly proceeding through the Indian legal system on WhatsApp. And the contention is that WhatsApp should give the encryption keys to the Indian state because they're worried that WhatsApp being ... WhatsApp is what the country runs on. Sitting in the US, you probably don't understand how important WhatsApp is. It's a bit like how China Tencent and Tencent Messenger is so central to the country. So we'll see how this goes. At some point they will understand and probably agree to some sort of middle ground. So I would say these three. A little bit of temperamental tax treatments, laws being applied, a little indiscriminately.

And the third thing that I was mentioning, Jim, is about economic nationalism. So if you keep into mind these three, temperamental tax treatment, treatment of laws in indiscriminate manner, and finally economic nationalism, these are sort of three ways in which the government sort of creates challenges, I would say. Yeah.

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

We are investors in a fund that concentrates on Bangladesh. And one of the GPs there said to me that Westerners get most things wrong there. And he gave us an example. He was talking to a potential LP and the LP said, "Yeah, well I was looking at adoption rates of internet in Bangladesh and they're microscopic. Nobody seems to be using the internet there." And he smiled and he goes, "That's because they don't ask the right question." If you look at a survey that says when was the last time you were on the internet? It might seem long to a Westerner, but if you asked the question, when was the last time you were on WhatsApp or when was the last time you were on Facebook, it was today because ... and this is echoing the importance of WhatsApp in India as well. And it seems to me that if the state really wants the country to emerge as an economic powerhouse, they would at least understand the universal importance of those apps. Or am I just a Westerner totally getting it wrong?

Sajith Pai:

Yeah, I think they do understand. It's just that I think there are very powerful forces, and it's not unique to India alone. We are seeing that in Brazil, we're seeing it in China. The state today, and sometimes egged on by the dynamics of politics internally and having to pander to a certain constituency sort of takes the stance that how can we surrender to the hegemony of the West? And we now need to regulate these. Sometimes it's good. I do appreciate that the EU has helped regulate Apple to change the lightning port to the USB-C port, and that's a godsend. I can use different chargers now. I'm not reliant on the Apple charger. But sometimes it can get overtly kind of awkward. And I do hope that some of this regulation doesn't lead to a situation which leads to someone exiting the country like X was forced to. So I don't know if it'll happen tomorrow in India, but yeah, I mean these are risks that sometimes you run.

But I think overall, I think India's far more progressive. I mean, I must tell you that, and I think there is a keen understanding that India is far more connected into the global economic system and India stands to benefit far more from it. And there are enough pulls and pressures, enough constituencies that sort of a middle ground will be reached in India.

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

Do you still see a diaspora of people of some of the brightest minds and who would make natural entrepreneurs? Has them leaving for places like the United States or other much more conducive to friendly laws and terms around venture, is that still significant or are you seeing that slow down?

Sajith Pai:

I'm not seeing it slow down at all. I'm actually seeing it rise in certain parts of India. If you go to Punjab, which is in the north of India on the border with Pakistan, historically it used to be India's most prosperous state. That's because it's fertile farmland. And they benefited from irrigation projects laid down since the British time. And they also did very well when we had what's called the green Revolution when we got these seeds. But over farming, over fertilization and many other challenges, including some use of terrorism, etc, has led to declining incomes, a lot of farmland being not productive anymore. And as a result, a lot of the youth in Punjab not finding gainful employment because industry has not grown there as much. As a result, a lot of Punjabis want to migrate out. And I was recently reading this podcast where the economist editors in India were being interviewed, and one of them spoke about how when you go to Punjab, almost every hoarding you can see is relocate to the UK. Apply to this university in the UK, Visa for UK, etc, etc.

So there are parts of India where that's particularly prominent. For example, the state I come from, Kerala, sends a lot of people to the Middle East. They work not always in white collar. A lot of it is blue collar, so similar to Punjab. So what we're seeing is the rise of blue collar migration has really gone up. When it comes to white collar migration, I think it is not the case that in the 60s, 70s, a lot of Indians migrated to the US because jobs were not hard to come by. So that's not true for white collar jobs are not easier to come by, but the absolute numbers have gone up because there are a lot more of them, et cetera, and there's nothing wrong in it. Many of them want to study things, many of them get scholarships. So it's net positive for everyone because many of them send money back too.

But what we're seeing in blue collar migration is something that's very interesting. And I do think a lot of it has to do with the challenging economic circumstances that they find themselves in. And I talk about the three E's in one of my reports, and one of them is English. So the elite Indians have access to English and use English as a proxy or English as a gatekeeping device. The second is exams. So one way to break into India One, for India Two people is to do well in one of the government exams. All government jobs are through exams. And it's crazy how many years sometimes people take to pass these exams. And effectively passing an exam guarantees you a regular income. And given that only about 50, 55 million people in India have regular income, you can imagine how big a difference. Just 4% of Indian population have regular income. The third E, the first was English, the second was exams, and the third is exit. When you don't have access to these two, then you look at exit as one way. And we're seeing large numbers of that.

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

And you wrote a very interesting piece that looks at what you call the English tax. Talk a little bit about that. And I find that piece very intriguing.

Sajith Pai:

Sure. So the English tax is essentially the fact that much of the Indian internet, much of elite India's communication, much of public science in India tend to be in English. When I say public science, I mean, it's changing now. So for example, if you go to a hotel and like a five star hotel, you will see most of the signs in English. If you go to a Starbucks in India, you won't see anything inside in Hindi or Bengali or Tamil. You'll see it only in English. When you go to Turkey or Germany, all of the signs will be in German. Some of them, tourists-

Sajith Pai:

... in German, some of them tourists, like in Istanbul you might see a little bit of English, but if you go into Ankara or something in Turkey, you'll only see it in Turkish. It's fine, because much of the population speaks... Very few people speak English. India, the fact that India One all speaks English and is fluent in it, mean that much of the signboards, et cetera, are in English. This concept of English tax came to me because one day I was sitting in the Bangalore airport, and I saw that almost every sign internally inside the Bangalore airport was English. But other than the transit signage, only the transit signage was in the local language, Hindi and English. But all the shops were in English, et cetera. And I said, "Imagine." And I saw a couple of people sitting there. There was an old man and a woman, they were wearing Indian dress, he was wearing a dhoti, a sarong equivalent, and she was wearing a sari. Okay? And they were old people and they were sitting peacefully and they seemed... I can't prove for sure, but they were speaking in Kannada, and I thought they probably weren't as fluent in English, and I wondered how intimidating this would be for them, everything in English, et cetera.

So, this is what I call the English tax. The English tax is something that we enforce on non-English speakers. A lot of apps in India are in English, a lot of literature that comes out, much of it is in English. So for example, if you don't have access to good English, you're shut out of a lot of writing. AI should change it, because translation is very expensive. So, hopefully AI will change some of these things for the better. So, this is what I mean by the English tax. The English tax is the preponderance of English across apps, signages, literature, so as to make it overwhelming for a non-English speaker, or non-fluent English reader to interface.

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

Yeah. And I really identified with that, because when I was in Japan in the late 1990s, the first call I made was back to my wife and I said, "I don't understand anything here." I felt entirely like a foreign man in a foreign land, because I couldn't even make a phone call. You would pick it up and they would give rapid-fire Japanese and you'd be, "English." And then it would just come rapid-fire Japanese. And when I was reading the piece, I was like, "Wow, I understand that feeling."

And I agree with you, that I think that AI and AI translation is going to help tremendously with that, but do you think that that was just a remnant of the English Raj, or is that also a gate-keeping mechanism?

Sajith Pai:

I think a lot of it is not gate-keeping as so much as just the fact that a lot of the elite Indians are very comfortable with English. It's worth noting that most of the, I would say, the formal jobs, I would say English is used, I would say about 50% of the time. About 50% of the time they'll speak in a different language. But if it is at the top, if it's really in senior management, for instance, largely English. All written communication is largely English. All emails are English.

I haven't got a single Hindi email. Not a single Hindi email, in all the years I've worked. And it is shocking, I would've expected at least one email to come to me. I've not got a single email. So, if you want to work in corporate India, you can speak a little bit of Hindi, or speak a little bit of Tamil, and that's fine, but any written communication is almost entirely in English. And so, it is not intentional. Yes, gate-keeping is an outcome of that, but what it does is if I'm comfortable in English, and I know that people come into these jobs, they come through the right colleges, they're comfortable in English, and it just turns out that people use English, and it's how it is.

There's a lot of path dependence that's really emerged, because when the British were there, the elite... So, there's this gentleman called Macaulay, okay? So, he was a kind of a British administrator and he spoke about creating a middle race of Indians who would be able to mediate between the Native Indian who didn't speak English and the British. And so, English speakers in India are what I call Macaulay's children. Okay. So, a lot of the people who did well were people who knew English and who got into the bureaucracy, who got access to the top jobs, et cetera. And so, that sort of continued. I don't think it's very intentional gate-keeping, but certainly it helps that only a certain percentage speak English, and these speakers get access to the best jobs. It's a happy outcome for the English speakers.

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

Yeah. And of course it's not unique to India. Part of the emergence after World War II was English essentially becoming the world's language, against many people's desires, of course, especially the French. But, for example, the most prestigious scientific journal in Germany is published in English, not in German, because of that universality. And I also think that English is a fairly easy language to learn how to speak poorly. It has a ton of idiom, especially American English is filled with idioms. I once had a guy who was a native Spanish speaker work for me, and he was telling me a story about how proud he was of... He's from Colombia, where he studied English and everything, and he had an MBA from a great institution here in the United States, and he had his first job. And he said he went and he was quite pleased and everything, and he said by the end of the day he went back and his wife said, "How'd it go?" And he was just crestfallen, because he looked at his wife and say, "I don't speak English at all."

And he was specifically referring to American English is richly idiomatic, like water off a duck's back, and things like that. And he was like, "Water off a duck's back?

Sajith Pai:

Duck's back.

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

"What does that mean?" And so, I think that that is part of the challenge with the emergence of English as the de facto world language. But you've also written about what you called one of India's newest castes, which is highly educated, affluent, but inter caste marriage, inter religion, marriage. And then you say the paradox there is they're at once the most, but also an invisible class. Talk to me a little bit about that.

Sajith Pai:

Yeah, that was my first big hit when it came to writing. I'd been writing for a long while and then I wrote this article, and it just went viral across India. I got a lot of fan mail and I got a lot of hate mail. And the fan mail came from people who said, "Oh my God, you have described me. This is my identity. I'm an Indo-Anglian." Every year I get one such mail now. It used to be a lot more earlier. The hate mail came from people who said, "You don't use caste so loosely, young man. You don't know anything about sociology, you don't know anything about politics, you don't know anything about..." And whatever. And, "You are just using caste like..."

Of course, I shouldn't have used caste so loosely, but what I was trying to say was typically the Indian caste system has Brahmins at the top. And I said there is a caste which is more elite than this... Sort of other way to look at it's to say that they're broken free of the caste system, and they're a parallel to that, because anyone can be part of this system, and all it requires is for you to speak English fluently. But the objection was that to speak English fluently, you need to be a member of the privileged caste. And well, it's hard for me to win in every argument. But essentially, for example, in my house, my family speaks in English. And one day we were in Hong Kong, and I remember we were speaking English, and a gentleman asked us, "Where are you from?" And I said, "India." "Okay, you are Indians, but where are you from?"

I said, "India." "Oh, but you speak so good English." I said, "Yeah, but..." I'm not the only person. I don't know the exact numbers, but I would say there is a segment which I call India 1A, or India Alpha, which is sort of a subset of India 1, about eight to 10 million households, about one third really of the households, 25, 30 million people, who speak English very fluently at home and are more comfortable in English than in other languages. And one way to become a member of this is typically be from when you and your wife are from different communities, and two languages. And often the kid speaks in English, because it's too confusing for the kid, and the husband and wife also don't know each other's languages, so they use English as an intermediating language. Like a lingua franca, as they say. And the kids start speaking that.

But me and my wife, we do speak a language called Konkani, but we don't speak Konkani as much. And my hypothesis is, I haven't been able to prove this, but I'm trying to prove this, is that Indian languages have fewer words which describe emotional situations or contexts. I was reading this podcast where Charles Duhigg, he is an author who has written this book called Super Communicators, where he talks about language having three components. There is the practical one, " Please get me this book." Then there is social, "How are you feeling, Jim?" And the third one is, "Jim, what you told me did not make me feel good. I think there was melancholy in what you said." Or something like that. Right?

So, the third one is a challenging area. For example, in the language that we speak I know enough words relating to the first practical context. I know enough words relating to the second social context. But when it comes to any emotional conversation with my wife, et cetera, where we want to talk about issues, et cetera, we tend to use English a lot, because English has far more emotional range. So, I'm willing to even pay a student to a PhD, or I'm willing to pay someone to do research. I want to find out how Indian languages rank by vocabulary. Do Indian languages have fewer words? B, do Indian languages have fewer words in the emotional bucket? Three, does the average Indian speaker have much more limited vocabulary, especially in the emotional bucket?

If what I'm saying is true, then that explains a lot of why the elite use English a lot more, because the native Indian languages don't have enough range, especially on the emotional side to express themselves.

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

Wow, that is such a fascinating thesis. Now you've given me something that I'm going to be thinking about for the rest of the day. Because I had a colleague who was Japanese, and I got to know him really well, and we were talking about language, and I asked him, "Do you think differently when you're thinking in English versus Japanese?" He looked at me and he goes, "Jim, I don't just think differently, I act differently." And I went, "Well, what do you mean?" And he said, "When I'm thinking in English, I'm much more proactive, 'We can do this. Let's go take that hill.'" And he goes, "When I'm thinking and talking with colleagues in Japanese, I go to a much more consensus oriented, 'Do you think that maybe taking that hill over there would be a good idea or no?'"

And so, I hadn't thought about it from the point of view of a lack of the ability to express emotions in that native language, because ultimately, I think that's one of the things people get really wrong about capitalism. If you are going to be an incredibly successful founder, you better understand emotions, because emotions are ultimately what drive a tremendous amount of decisions, even for so-called rationalists. What they'll do is they'll make an emotional choice to buy a product, to subscribe to a service, et cetera, and then they'll paper it over after the fact with all the rational reasons for why they pick that particular product, and or service. And so, that is really fascinating, and I will be thinking a lot about that.

You also mentioned something that I found really interesting, especially given the fact that you, in your three E's, exams being so important, and credentials being so important, you once said that you would rather get rid of the degree on your CV than stop writing. So, this is kind of a two- pronged question. You've also mentioned that there aren't very many Indian venture capitalists who do write a lot like you do. So, my first question is why is that? And then secondly, I am fascinated that given how important externally exam results and credentials are, you understand that the writing is even more important, and I'd like to hear your version of why.

Sajith Pai:

Sure. We'll take the first one, why VCs don't write. I think it's got a lot to do with the fact that in India, while the venture industry is reasonably sizable, and there are a rising number of VCs now, I think the power imbalance is still much more in the VC's favor, unlike the US where the power imbalance is in the elite founders favor. In India too, it is changing, but slowly. So, what happens is when there's a power asymmetry in the VC's favor, the VC can sit back and wait for the founder to approach him or her. In the US it's such a large market with so many founders, and the market is relatively uncapped.

That means if you miss out on something that's big, that could be 100 billion dollars or more. Whereas India is relatively capped. The sense we have the largest Indian venture is $36 billion, which is Flipkart, majority owned by Walmart. The next one is half the size, Zomato. And the third one is one-fourth the size. So, relatively mistakes haven't been as expensive as in the US. When the power asymmetry changes, for example, there are a lot more elite founders, and those elite founders then have to pick you, which is how great venture happens, you have to be picked by the founders. It's unusual that someone once described venture as not an asset class, but an access class, where the trick is really getting access to the best founders, and the only asset class where the asset picks the investor, which is sort of the founder.

So, now in the US, I'm not surprised that many VCs are writing, because they're signaling to the founder, "Hey, I'm relevant for you. I know this space, et cetera." They're trying to make themselves useful. In India, I think they're some ways off from that because relatively the VCs have more power, and the founders have to go to them, and there are much fewer quality VCs, and every founder knows that, unlike in the US where there are many quality VCs. And in India, there are much fewer quality VCs, they have no choice but to go and... They can't be pickers. There are few founders who can be pickers, because they're second time founders, et cetera. It's changing, but it's slow. So, this is one reason why VCs don't have to market themselves. I, however, choose to market myself through writing. And for me, writing was the one way I could make an impression.

I remember reading this Scott Adams article about how to be The Only, where he said that, "Look, from many Japanese speakers, there are many marketers who... But if you are a Japanese-speaking marketer in the US, then you're unique. So, you'll be the only." So I said, "I will never be the best VC. I don't know, maybe I will, but as of now, I don't know if it's a realistic ambition to have. I will never be the world's best writer, but can I be the worlds best writing VC? Okay, that's tough too. But can I be India's best VC who writes? Yeah, I think so." Yeah, and I think that's the slot I've carved out. And it's worked for me, because I came into venture at the age of 43, I had not been a founder. I had not worked in a startup. I had not been an investor. And I sometimes don't know what Karthik Reddy saw in me.

Of course, he has told me what he saw in me, who was a person who reached out to me. He founded Blume. But he did reach out, and I heard him out and I said, "Yeah, sure, I'd like to give Venture a shot." and it's worked well for me. But because I was like an outsider coming into venture, I wanted to market myself to founders, and I wanted founders to find me, and hence writing became very critical. And the reason why exams don't matter enough is I feel like that doesn't help me stand out as much, because even if I pass the toughest exam in India, just typically the IIT entrance exam, okay? It is not going to make me stand out because there are many VCs who are from IIT, but there are very few VCs who write, and that's what helps me stand out.

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

Very smart. And that also leads me to what skill sets did you bring from your longer history in entertainment and media that were immediately applicable on the venture capital side?

Sajith Pai:

I worked for a long time in a company called The Times of India Group. It is India's largest newspaper company, sort of like Gannett in the US. Very well run, privately held, very profitable. And there was a... Well, there's no word for it, but there was a way of... And company's, the name was Bennett, Coleman and Co. Limited, the official name, because it was a British company which was acquired by Indians. They kept the name Bennett, Coleman Co. And they were of... The term was, there was a Bennett approach or the Times approach to look at the business, through a lens. And we worked with this gentleman called Sameer Jain, who's the owner of the group. And he's a brilliant mind, and he looks at the world in a very unusual way. And there were a lot of principles that he looked the world through, which I learned. I used to work with him closely.

I was the chief of staff for a while, and this Bennett approach, or the Bennett way, or the Times way was something that I brought in. In addition, I think working for about two decades, you've worked with a lot of people. And for example, I had worked with a lot of salespeople, and I understood that incentives matter a lot. And one of the unusual things I found was startup founders did not pay attention to incentives. So, I would ask them, "Okay, this is the goal, which is to enter this market, and who's driving this?" And so, they'll say, "XYZ." So, I would tell him, "Okay, if this succeeds, how much will XYZ make?"

They would say, "Why would he make more? He has ESOPs he would make." Now I would say, "Okay, but he'll make that, even if this doesn't succeed and the company does well." And I would find that there was a blind spot. And I would say like, "Oh, okay." Or for example, I would say, "You need to set the incentives such that this person makes money only if the next person's incentives work." If I'm the salesperson, and if you pay me well, if you pay me my incentive, but once I convince the customer to give them money, I just take a ticket, but the onboarding is a failure and the client then walks away, I still get my money.

And I would say, "How can you design your incentives like that? You need to design your incentives that you only get money after six months, nine months, et cetera, when the customer's onboarded and it's a working partnership, et cetera." So, I think incentives was another area where I was able to really help my founders.

The third one is really strategy. And I find that sometimes bringing the lens of strategy was very helpful. A lot of founders sometimes intuitively get it, but they're not business students. They're not studied business. And I find that this is sort of, I would say, a gray area for them. And these were the areas, strategy, incentives and this unique times approach to looking at data, for instance. Where we would say, "Don't look at the average, break up, de-average everything, and really look at what is really working and what is not." Not that founders wouldn't do it, but I was able to stress that to a greater degree.

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

And that's part of what you also call Narrative Capital, right? Where they have a strategy, they have the incentives, right. And what you're helping them do is tell the story better. And listening to you, it sounds like helping them understand, gee, these things over here really, really matter, and you need to think about them more. Are you finding that there's pushback on that from your founders? Or are they just, "Thank you, thank you."

Sajith Pai:

No, no, they push back. Founders, they have the mind of their own. And in India it's extraordinarily hard to start up. It's a very difficult place to do business, which is why when Indians come to the US, they just find that, look, it's such an easy country to do business in. If you take care of the basics, you-

Sajith Pai:

... in. If you take care of the basics, you will do well. They just can't believe it. The taxman is grading them, et cetera, et cetera. But India is a hard creator to business in. So it takes a special kind of person to be a founder in India. And I would say that I don't have it easy with any founder, and I'm grateful for that. I don't want any founder to just accept what I say at face value. I love it when they push back and then I can push back. And finally, end of the day, it's their business. They need to run it. They are the, as Roosevelt says, men in the arena, women in the arena. And I respect that. I'm the person on the stands. But yeah, I got to be a mirror for the founder. I got to show his or her face warts and all so that they're able to take the corrective measures.

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

And you've also said that really India is kind of a digital warfare state. What exactly do you mean by that?

Sajith Pai:

Yeah, digital welfare is a term that's kind of coined. I don't know who coined it, but I like it because it describes two parts. One is digital and the other is welfare. So digital means, digital public infrastructure is one of the big innovations that India has done in the last, I would say decade and more. Digital public infrastructure stands for broadly, digital Lego blocks, basically product sets around identity, payments and data exchange. So identity, all Indians have something called an Aadhar number, so like a social security number, but an Aadhar number, didn't exist. Payments, we have one of the most frictionless payment system called UPI where I can send money like a message.

There were about, I think 15 billion transactions that happened last month on UPI. It's crazy, right? Yeah. 15 billion transactions. The third is data exchange. For example, I don't need to carry physical copies of many documents like my driving license, my identity card. I have something called DigiLocker where I can store it. And now the beauty is people can access their digital document and remotely if I give them the right, and this can be used for other services like what's called the know your customer, KYC, which is needed for financial transactions, et cetera.

The most important thing in this is digital payments. And the digital payments and the welfare state, that is a lot of Indians are poor, and what the government has done is use the digital payment infrastructure and the fact that people, a lot of people are economically less better off to give subsidies to them rooted through this. So digital welfare state is really what this particular government, Mr. Modi has done well. They have reinvented India as a digital welfare state where while there is a certain DNA of socialism making sure, and they need to, it can't be hard capitalist because India is not a country which is 2000 rupee per capita income, large masses in poverty. They have to take care of them. And what they've done is cleverly used the digital public infrastructure and digital payment infrastructure to drive the welfare. And that is why I call India digital welfare state.

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

And you also refer to, it sounds like you've mentioned a lot of things that in what you've called Tony Wang Trifecta. And essentially that's cheap bandwidth, smartphones, and frictionless payments. Smartphones in every pocket. And that was a huge inflection here in the United States as well. When the iPhone, for example, in 2011 started putting GPS in the phone itself, that opened up a huge number of markets that would've been impossible prior to that, right? Like Uber, Lyft all of the delivery services, et cetera. And are you seeing things right now, if we have some listeners who are thinking, "India looks like a very attractive market." You have said, "It's not for beginners," but what are you seeing emerging from that trifecta and that welfare, digital welfare that you see as could be a very, very big thing over the next 10 years?

Sajith Pai:

Yeah, so a lot of these examples, like the digital welfare state, et cetera, has come from this particular publication that we do, which is what kind of very well known here, it's called The Indus Valley report, and it's online, you can access it. So in The Indus Valley report, the latest one, which we published around late February, March every year, what we did is we actually cataloged interesting examples of digital public infrastructure. So there's something called AutoPay, UPI AutoPay. UPI is really the payment thing, so UPI has AutoPay system where, so if you're a subscription product for instance, a customer can set it and then they don't have to think about it. And what that has done is led to growth for a lot of companies, which earlier struggled with getting customers to pay. And there were a lot of Indian, interesting, I'll give you two examples.

So there was a company called ShareChat in India, and ShareChat, think of it as Twitter or Instagram, but in non-English languages. So they have different channels. Each language is a channel. And so you go into your channel and get a lot of content. And ShareChat struggled with monetization because they tried to make money, so advertising, but because a lot of the people who are on it are not necessarily affluent Indians, so they couldn't monetize those users. However, of late, a lot of Indian media apps have started to monetize. So we have a company called Stage, which does vernacular content, and they've been able to monetize furiously. What made the difference was UPI. So customers could not only pay UPI frictionlessly, they could pay very small sums, but this again goes back to sachetization. It's just $5 for the year. And content is produced very cheaply because they work backwards from what customers can afford to pay.

And UPI AutoPay means customers subscribe, then they just renew. So I've kind spoken about how stage leveraged UPI AutoPay here. I won't go into detail, but then for example, we've invested recently in a company called Namma Yatri. And Namma Yatri means our travel. And sort of think of it as Indian Uber, but the differences as follows; Namma Yatri is built on an open source protocol called the Beckn Protocol. And the Beckn protocol is created so that companies like Namma Yatri and others could leverage this protocol for logistics, transport of goods, or transport of people. And they have pioneered a very interesting model where they actually charge 25 rupees, which is sort of 30 cents every day to an auto rickshaw driver, which is like a tuk-tuk, and eventually they'll get into cars as well, but they don't charge anything to the customer. So this different to Uber where Uber, if I pay Uber takes 20% of the cut.

So this is actually a different model, and it was made possible only thanks to the digital public infrastructure that came about. So I would say if you're in the US, and you and anyone can operate on this, Uber in fact is thinking about how to leverage the Beckn protocol. What I would say is digital public infrastructure and a lot of the digital public goods that are emerging, whether it's Aadhaar for identity, UPI for payments, data exchange through DigiLocker, et cetera, and a lot of the other goods.

Now, for example, health, there's something called ABHA, which I won't get into the full form of that, but essentially it's like all your health records are available. Then you have Account Aggregator network whereby if I'm a business and if I need to get access to debt, like booking capital loans, I can show that I can give access to my bank account. It's tokenized, and the bank can see that, "Hey, he gets regular payments and this is enough of a credit history for us. We don't need to ask him to mortgage his house or anything like that." Historically, the challenge has been that India is under-penetrated on credit because a lot of credit in India is given only on the back of assets. Now, because land records are so poor in India, homes cannot be mortgaged unless you typically have you a member of the elite middle-class or upper-middle-class. That is why gold is very popular in India. Why do Indians hoard so much gold? Why is India a sinkhole for all the gold in the world? Because gold allows me to get access to debt. So there are all of these interesting... Also, the fact that we spoke about trust, low trust also manifests itself in a poor credit market, because I'll not believe you and I'll not believe your credit history, but I want hard assets. But now things are changing because your credit history is now visible, it can be accessed more easily. And what the government is trying to do is bring more people into the formal economy through this route.

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

That's fascinating because another one of the thesis that I have is that in the United States, we are in many respects, hampered by our very efficient past. And I use our installed landline system, right as digital was coming online. And Americans, the adoption curve in America for digital was actually quite a bit slower than the rest of the world, and one of the reasons for that was the rest of the world did not have the kind of really efficient infrastructure that the United States had developed. So in a way, it hampered our ability to embrace the new digital networks and digital payments and all of those types of things. What are another few examples that you would think that would fall into this line that it doesn't get developed in the US because we already have that infrastructure that you can take advantage of in India that wouldn't be obvious to an American investor.

Sajith Pai:

One interesting example I would say is broadband internet or wired internet. We have just about 30 million wired internet connections in India, about 20 million wired phone lines in India, fixed phone lines. It's just plummeted, people are giving it up. My parents had a wired phone, Jim, there was a time when we had to wait 10 years to get a phone line, I kid you not. In the eighties, seventies, and the eighties when India was socialist, it was so difficult to get a phone. I remember that we would get a phone call, we would give the number of the neighbor and phone calls would come saying that somebody's passed away or something like that, and those are only emergency calls would come, or somebody's passed an exam or somebody's getting married, and then my father would go. Then when he hit a certain level and his government job, he got access to a house with a phone, then he got access to a car.

So I've seen how hard it's to get a phone line, and then one day it all changed. Anyone could get a mobile, if you put in the money, you would get a mobile. And so we've just have about 18 or 20 million phone lines in India, whereas the US has far more. And because India is a leapfrog nation, you just leapfrog to the mobile handset Wi-Fi, like I'm having this conversation over Wi-Fi. But a lot of Indians don't use Wi-Fi, they use mobile internet because Wi-Fi means your house has to have good power, regular power, and if you don't have regular power, then you can't take really advantage of Wi-Fi because it comes and goes. So only what, 30 million Indian houses have wired broadband. Credit cards, only 40 million Indians have credit cards. And 40 million Indians, they have two, three cards. So about a hundred million credit cards in India. It's very small. What we really leapfrogged to is the mobile internet, mobile payments, and which is like UPI. So India is a leapfrog nation. And I think that's another metaphor for India, which I like to use.

Jim O’Shaughnessy:

Yeah, I think that's the way I think about it as well. So what are you most excited about in terms of both the ability to leapfrog and sort of the novel way, what companies are really you looking at and you're just like, "Here's a classic example where we get to leapfrog and also this is an amazing idea."

Sajith Pai:

So I would say one way, that's one trend line, that is happening in India is a move from unorganized to organized. So there are ways of doing business, which is on paper, which is on trust within a small community, on high interest rates. Because our long payment cycles, which is now changing because you can use a mobile phone to transact between each other, you can use the mobile phone to discover each other. So one wave that I'm seeing is really more and more Indian commodity markets coming online. So we are beginning to kind of see that. This is really one clear tendency. The second is that you can, so B2B marketplaces is the most obvious manifestation of that trend, which is unorganized to organized, because earlier you would do a transaction in a particular region between trusted groups, et cetera. Now you can do transactions all India, et cetera, someone can vouch for that. So that is something we are quite excited about.

Apart from that, there are also, I would say very interesting, unique Indian models emerging, which are, you'll not find it anywhere else in the world. It's a combination of access to the mobile and the unique UI and UX that it enables, as well as the nature of India as a low trust country, the type of technologies that are available, et cetera.

So one is, there's an interesting company called FRND, F-R-N-D, and they're a dating app, but dating here doesn't work the way dating works in the US here are the challenges that the two genders don't mix as much. So FRND says, "Don't worry about dating, let's get you talking. And what it does is it creates a chaperone who will help the two play games and get comfortable with each other when the chaperone is there. And then if you want to DM directly, then you go to pay up something and sort of stuff like that.

There's an interesting app, a called Sri Mandir, it means temple, honorary temple, whatever. And it's fascinating because Indians like to do what's called Pooja, which is, and they can attend virtual temples and do Pooja, and that's a very unique Indian kind of. Then there's an app called Jar, which is where people can save small savings and you can transfer it and then buy gold with it. If you transfer 40 rupees it will buy 40 rupees with digital gold.

So the very interesting uniquely Indian apps born out of Indian consumer psychology, unique interfaces that Indian internet offers as well as the low trust nature, et cetera. So I'm quite fascinated by all of these trends and be really looking at these spaces. So one company we bet on and which succeeded well was Stage, which just mentioned, which is really about vernacular content. So sort of like Netflix for India, but they have very distinct Indian content and produced extremely cheaply, and they cater to people who don't get the kind of content that they would like to enjoy, and now they get access to that. So these are all opportunities that I'm excited about.

Jim O’Shaughnessy: