“To be ignorant of what occurred before you were born is to remain always a child.”

— Marcus Tullius Cicero

"Every generation laughs at the old fashions, but follows religiously the new."

— Henry David Thoreau

Insufficient context leads to a significantly limited perception of the world around us.

Articles and thought pieces I read all too often judge a historical figure or idea by the generally accepted standards of today, ignoring the prevailing views of the society in which that person lived, acted, and thought.

Art offers us an excellent example. The Uffizi Museum in Florence houses some of the greatest masterpieces from the Italian Renaissance of the 15th and 16th centuries. One such masterpiece is Sandro Botticelli’s painting, the Primavera:

While beautiful to modern eyes, the Primavera can only be fully appreciated with an understanding of its context, including the early Renaissance love poem upon which some scholars claim it was based.

Such context unlocks many of the painting’s secrets, from the way it needs to be read (left to right) to what each figure represents allegorically (note the naked nod to its patron, Lorenzo De Medici, who is depicted as Mercury on the left, pointing to Heaven).

Studying the Primavera with this knowledge reminds us that, to fully understand our own place in history, we must understand that of our ancestors: how they thought and what moved them to act, believe, and behave as they did.

Context isn’t just relevant to the era in which an idea, person, or artwork originates. Each generation that subsequently interacts with that thing brings its own set of beliefs and perceptions to the table.

For example, paintings like the Primavera were of NO interest to people around 200 years ago. The patrons of the Uffizi didn't even look at the painting until the 1880s!

The poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822) visited the Uffizi daily in Florence and only took notes on the sculptures. Why? In his era, sculptures, not paintings, were deemed the most important art form.

Consider the Medici Venus, a Roman copy of a 4th Century BC Praxitelean sculpture of Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love:

The Medici Venus was removed from public display by Cosimo De Medici III for fear she might corrupt the morals of art students (!?)

For centuries, this statue remained a potent sex symbol for educated Europeans. It was the *only* statue in Florence that Napoleon brought back to France with him. As late as 1858, Nathaniel Hawthorne, author of The Scarlet Letter, panted heavily as he approached her.

Look at her again.

How in God's name did a statue that, to modern eyes, isn't even *slightly* titillating cause such rapture and heavy breathing in those from an earlier era?

Simple. By understanding context, we see that sometimes things are ‘important’ only because everyone in society thinks they are.

Moving forward in time, numerous Impressionist paintings are now seen as masterpieces. It wasn’t always this way: many are unaware that the movement's name was bestowed as an insult by the then fashionable ‘powers that be’ in the French academic school of art, who commented on the paintings only to deride and ridicule them.

Vincent van Gogh is considered one of the greatest painters of all time and yet sold only one painting during his life, The Red Vineyard, to the heiress Anna Boch for what amounts to $2,000 in today's dollars:

No one, even the connoisseurs and ‘experts’ of his era, ascribed much value to his work because they weren't conditioned by the societal belief systems of that time to be able to ‘see’ its value.

Today, the painting would probably sell for over $100 million.

My point is simple: it's easy for we citizens of 2023 to laugh at or judge things of earlier eras by today’s prevailing beliefs and standards.

This is the wrong way to approach the past.

By understanding the context of beliefs and events of past eras, we develop a much better mental model for how we should think today.

We are also forcefully reminded that people a few hundred years from now may look at many of our beliefs and customs and laugh out loud at how wrong or ‘primitive’ they were (are).

To truly remove yourself from the dominant thinking of your era requires you to constantly and ruthlessly challenge all of your beliefs.

This is EXTREMELY hard to do consistently.

It requires constant uncertainty and the willingness to always be open-minded to ideas. Simultaneously, it requires you to remain predisposed to data and let a model's consistency be your guide.

As Jed McKenna said, "If the facts are at odds with the theory, the theory is wrong.”

This goes against almost every fiber in our being. We hate uncertainty, allow ourselves to become prematurely certain, sniff out the data that supports our beliefs, and ensconce ourselves in the ‘tribes’ that share our values.

Though the process of breaking free may be hard, if you can do it, it becomes a superpower for understanding why we think the way we do and how this may change.

Such understanding is powerful. As Ludwig Wittgenstein said, "to understand is to know what to do." Improving your perceptions and mental models pays enormous dividends. It allows you to ‘see around corners’ and understand things that very few others do.

Is it worth it?

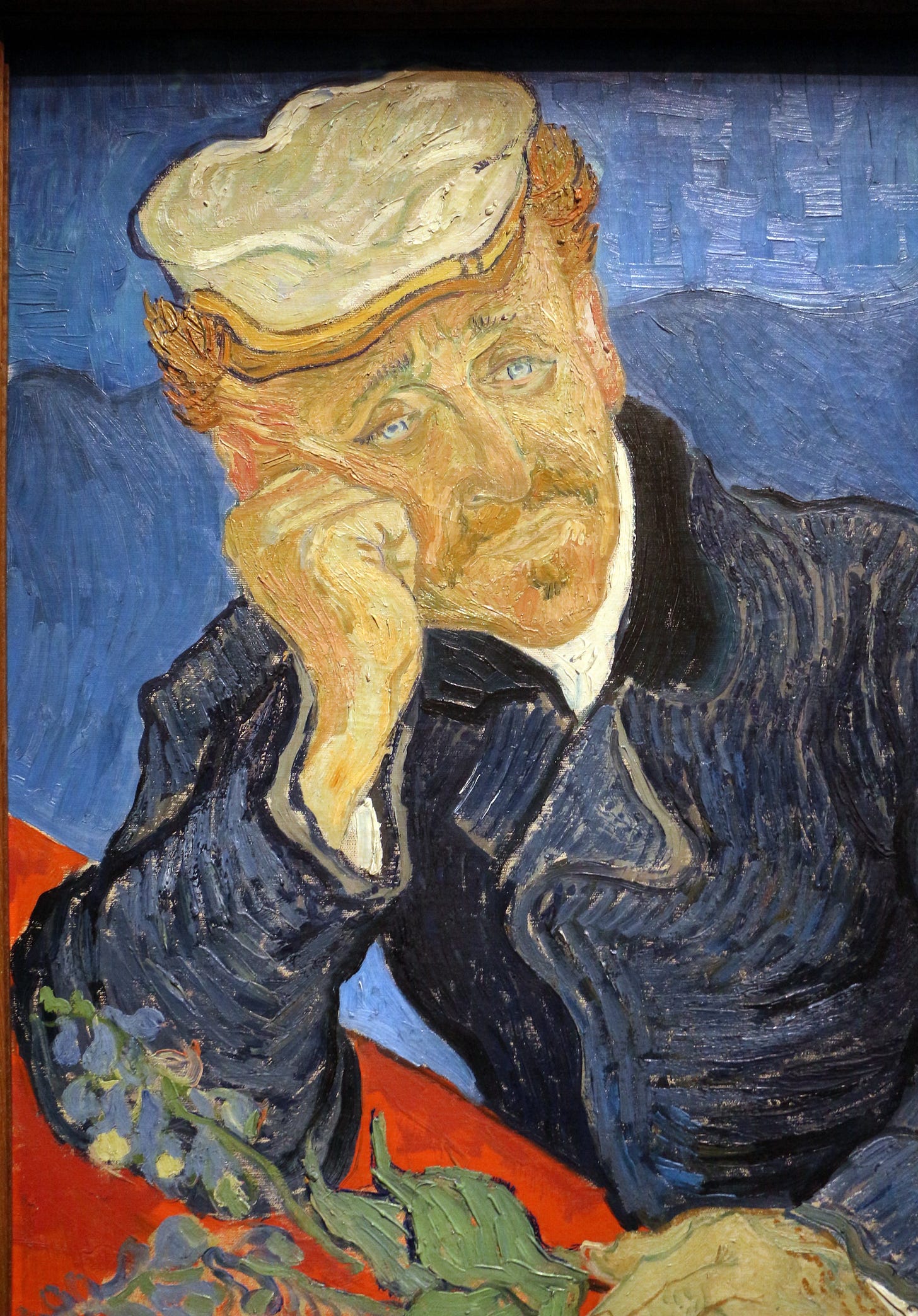

Let's revisit Vincent van Gogh. His Portrait of Dr. Gachet was originally sold in 1897 by van Gogh's sister-in-law for 300 francs (approximately $50):

93 years later, the painting was resold by Christie's New York to Ryoei Saito, honorary chairman of Daishowa Paper Manufacturing.

The price?

The equivalent of $162 million in today's US dollars.

So, yeah, it's worth it.

Great stuff! 💚 🥃

If Van Gogh could have lived for just another 100 years...Good piece, Jim!